ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a rarely occurring disease in the pediatric population. We report our center's experience of management of HCC in children and adolescents.

-

Methods

From 1996 to 2012, 16 patients aged 18 or younger were diagnosed with HCC at our center. The medical records of these 16 patients were retrospectively reviewed.

-

Results

There were 9 boys and 7 girls. Median age at diagnosis of HCC was 14.5 years. All patient had pathologically confirmed diagnosis of HCC. Three patients had distant metastasis at the time of HCC diagnosis. Eight patients were surgically managed, including 4 liver resections, 3 liver transplantations, and 1 intraoperative radiofrequency ablation. The remaining 8 patients received systemic chemotherapy. Overall, 6 patients are alive at median 63.6 months after diagnosis of HCC. All survivors were surgically managed patients.

-

Conclusion

HCC is a rare disease occurring in childhood. Patients with systemic disease have poor outcome. Liver transplantation may be a good option for treatment of pediatric HCC.

-

Keywords: Pediatrics; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Liver transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric primary liver tumors are a rare disease, accounting for about 1% (0.5%–2%) of all childhood cancers [

1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes 25%–30% of primary malignant liver tumors in children, and is the 2nd most common malignant hepatic tumor after hepatoblastoma [

23]. Whereas in adults HCC in cirrhotic livers is common, childhood HCC with chronic liver diseases leading to cirrhosis (e.g., chronic HBV/HCV infection, tyrosinemia, alfa-1-antitripsin deficiency, etc.) is about 30%–40%. In fact, 60%–70% of childhood HCC, develops within a normal liver [

12345].

Conventionally, surgical resection is recognized as the 1st line curative procedure for HCC in children, similarly as in adults. However, surgical resection is not possible in more than 50% of patients, despite of preoperative chemotherapy. Moreover, in children, after surgical resection, a high recurrence rate is observed, leaving less than 30% of patients cured [

1267].

Several recent studies have shown that liver transplantation after total hepatectomy may offer superior survival than conventional surgical resection [

8]. But, these consist of small, single-institution reviews. No study has compared survival after resection and liver transplantation for pediatric liver tumors while adjusting for patient and tumor specific factors [

910111213]. In addition, the value of the Milan criteria, the criteria for selecting candidate of liver transplantation with HCC, has not been verified in the pediatric population undergoing liver transplantation [

141516].

The aim of this study is to retrospectively analyze a single center's experience of management of HCC in children and adolescents.

METHODS

We conducted this study in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center. The informed consent was waived.

From 1996 to 2012, patients under age 18 with HCC as their primary diagnosis in our center, were analysed retrospectively. Sixteen patients were included.

Various factors such as age at diagnosis, sex, number of lesions, mass size, metastasis, treatment, recurrence, survival period, laboratory report, vessel invasion, underlying disease were reviewed from medical records.

Treatment method of each patient was determined individually by a multidisciplinary team consisting of pediatric and transplant surgeons, pediatric oncologists and radiologist. The patient's parents were then consulted and informed of treatment options and possibilities of radical tumor resection and long-term prognosis.

RESULTS

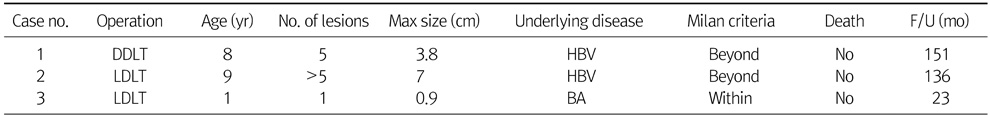

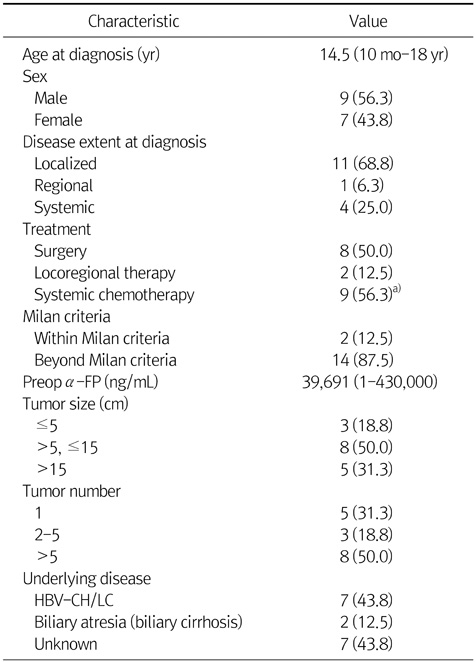

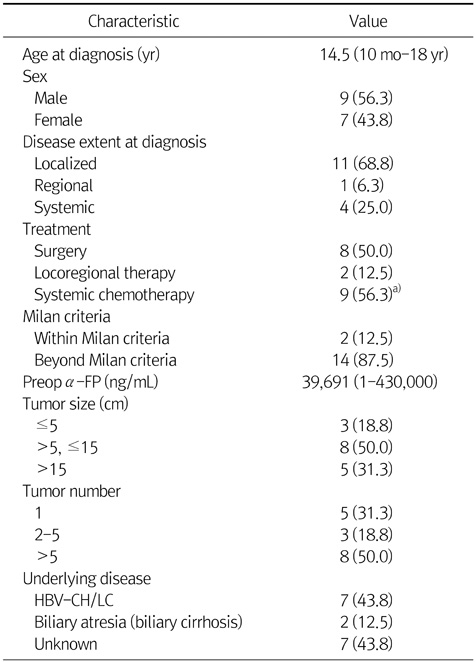

Table 1 presents basic patient characteristics. Median age at diagnosis of HCC was 14.5 years. There were 9 boys and 7 girls. Fifteen patients among 16 pathologically confirmed diagnosis of HCC and the other one patient was diagnosed HCC by CT image. Four patients had distant metastasis at the time of HCC diagnosis. Eight patients were surgically managed, including 4 liver resections, 3 liver transplantations, and 1 intraoperative radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Only 2 patients were within the Milan criteria when they were initially diagnosed. Median preoperative α-FP was 39,691 ng/mL, but 3 patients were within normal range. Three patients had tumors less than 5 cm, and the tumors of 8 patients were between 5.1 to 15 cm. Five patients had huge tumors larger than 15 cm. Seven patients were HBV carriers and had underlying liver cirrhosis. Two patients had biliary atresia. The other 7 patients had no underlying liver diseases.

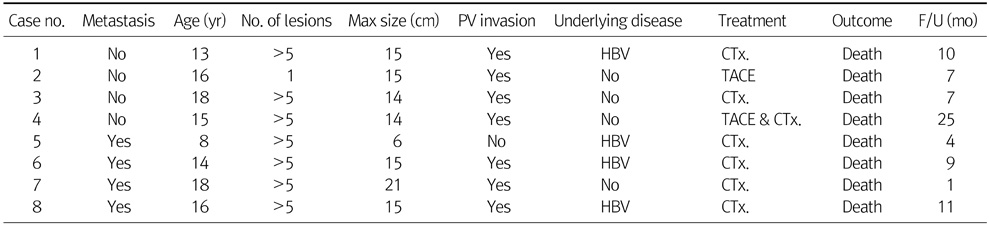

Table 2 presents 8 patients' data of non-surgical cases. Seven patients had multiple lesions and had been treated by systemic chemotherapy. One patient was treated by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and systemic chemotherapy both, and another one was managed by TACE only. One patient who was treated by TACE only, had single large HCC lesion with inferior vena cava (IVC) and portal vein invasion. At that time, our medical team judged it is impossible to make operation because of IVC invasion. Four patients had extrahepatic metastasis. Three patients had multiple lung metastasis and 1 of 3 had also bone metastasis. The other one patient had peritoneal carcinomatosis. All the patients who were treated by non-surgical method like systemic chemotherapy or TACE died from disease progression.

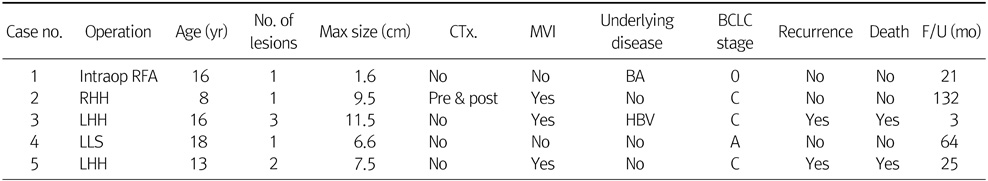

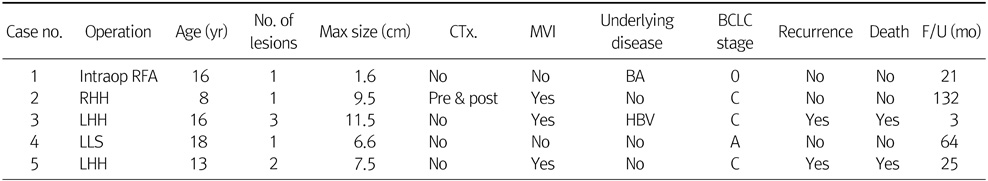

Table 3 shows 5 patients' data of non-transplantation surgical cases. One patient with biliary atresia was diagnosed HCC by CT image and was treated by intraoperative RFA. Another one patient received systemic chemotherapy before and after surgical resection. Two mortality cases occurred among surgical cases. These 2 patients corresponded to advanced stage C by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. They received left hemihepatectomy and after surgery, had recurrence and eventually died due to their recurrences.

Table 4 shows 3 liver transplantation patients' data. Among 3 cases, 1 case was deceased-donor liver transplantation and 2 cases were living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Two patients had multiple lesions and these 2 patients corresponded to beyond Milan criteria. One LDLT case that was beyond Milan criteria received systemic chemotherapy before liver transplantation. The other LDLT case had biliary atresia and received liver transplantation to treat biliary atresia and a HCC was incidentally detected by histologic examination. All 3 cases undergone liver transplant are alive without recurrence at the time of analysis.

Overall, 6 patients are alive at median 63.6 months after diagnosis of HCC. All survivors were surgically managed patients, either by liver transplant or resection.

DISCUSSION

HCC is a rare disease in childhood, and for this reason, the experience in the management of pediatric HCC is limited. SIOPEL-I study has shown a partial response rate to chemotherapy in 49% of patients and an overall survival at five year of 28% [

7]. In those who had a response, the resection rate was 61% compared with 5% in non-responders. Long-term survival was 33% vs. 0%, respectively. Many studies showed that only 50% to 60% of children with HCC are operable and less than 30% of children with HCC can achieve long-term disease-free survival with standard treatment [

7]. In our data, 7 patients of 8 non-surgical patients were in-operable cases and long-term survival of surgical vs. non-surgical group is 75.0% vs. 0%.

Many studies recommend early consideration of liver transplantation for pediatric HCC as the main treatment option. Also, some studies protest that liver transplantation in pediatric HCC is a good option for treatment even in outside-Milan cases [

17181920]. In the study by Ismail et al. [

17], 8 of 11 liver transplantation cases had large and/or multifocal tumors and some cases also had angioinvasion and local extrahepatic extension. However, the survival rate in this study was 72%, which is better than that of conventional liver resection for HCC in the study by Ismail et al. [

17]. However, good results of liver transplantation despite exceeding Milan criteria in children should be confirmed by analysis of a much larger group, which is possible only by multicenter cooperative studies. Our data includes 4 resection and 3 liver transplantation cases. Two patients undergone resection died due to recurrent disease, on the other hand, all liver transplantation cases are alive without disease recurrence. Furthermore, 2 of 3 liver transplantation patients were beyond the Milan criteria.

Unlike adult cases, the majority of HCC in children occurs in the absence of concomitant cirrhosis [

1821]. Thus, considering the shortage of donor organs, it may be a reasonable choice to resect the HCC lesion in those who have hepatic reserve and can tolerate a significant anatomic resection. But, in fact, many data suggest that survival for children with HCC may be better after liver transplantation than after resection [

18]. So when there is no extrahepatic metastasis and a liver donor is available, total hepatectomy and liver transplantation may be considered as primary surgical treatment. On the other hand, patients with chronic liver diseases (e.g., chronic HBV/HCV infection, biliary atresia, tyrosinemia, alfa- 1-antitripsin deficiency, etc.) should be screened with α-FP and by imaging techniques to detect tumor at an early stage. Early detection makes earlier liver transplantation possible without the need for chemotherapy [

17].

One of the LDLT cases mentioned in our data had biliary atresia and received liver transplantation to treat biliary atresia and a HCC was incidentally detected by histologic examination. Preoperative imaging with ultrasonography and abdominal computed tomography imaging was performed but was not able to detect any malignant lesion. Some reports recommended routine screening for serum α-FP level for the diagnosis of liver malignancy [

22]. Although the occurrence of HCC in an infant with biliary atresia younger than 1 year is extremely rare [

2324], in order not to miss small HCC lesions, preoperative screening tests such as serum α-FP level of patients with chronic liver diseases may be helpful for the diagnosis of liver malignancy [

25].

It is important to determine what tumors are most appropriately treated with liver transplantation. In adults, the Milan criteria (single tumor <5 cm, no more than three tumors & each tumor <3 cm) is used for this purpose. However, this criteria was developed in adults with cirrhotic liver disease, so the value of Milan criteria has not been verified in the pediatric population undergoing liver transplantation. Thus, a new criteria is needed to choose appropriate pediatric HCC candidates for liver transplantation.

In conclusion, pediatric HCC is a rare disease and patients with metastasis will be expected to have poor outcome. Surgical treatment, especially liver transplantation may be a good option for treatment of pediatric HCC.

NOTES

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Darbari A, Sabin KM, Shapiro CN, Schwarz KB. Epidemiology of primary hepatic malignancies in U.S. children. Hepatology 2003;38:560-566.

- 2. Bellani FF, Massimino M. Liver tumors in childhood: epidemiology and clinics. J Surg Oncol Suppl 1993;3:119-121.

- 3. Reynolds M. Current status of liver tumors in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 2001;10:140-145.

- 4. Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 2004;127:5 Suppl 1. S35-S50.

- 5. De Potter CR, Robberecht E, Laureys G, Cuvelier CA. Hepatitis B related childhood hepatocellular carcinoma. Childhood hepatic malignancies. Cancer 1987;60:414-418.

- 6. Czauderna P. Adult type vs. childhood hepatocellular carcinoma--are they the same or different lesions? Biology, natural history, prognosis, and treatment. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002;39:519-523.

- 7. Czauderna P, Mackinlay G, Perilongo G, Brown J, Shafford E, Aronson D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2798-2804.

- 8. Otte JB. Progress in the surgical treatment of malignant liver tumors in children. Cancer Treat Rev 2010;36:360-371.

- 9. Arikan C, Kilic M, Nart D, Ozgenc F, Ozkan T, Tokat Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children and effect of living-donor liver transplantation on outcome. Pediatr Transplant 2006;10:42-47.

- 10. Beaunoyer M, Vanatta JM, Ogihara M, Strichartz D, Dahl G, Berquist WE, et al. Outcomes of transplantation in children with primary hepatic malignancy. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11:655-660.

- 11. Kosola S, Lauronen J, Sairanen H, Heikinheimo M, Jalanko H, Pakarinen M. High survival rates after liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pediatr Transplant 2010;14:646-650.

- 12. Malek MM, Shah SR, Atri P, Paredes JL, DiCicco LA, Sindhi R, et al. Review of outcomes of primary liver cancers in children: our institutional experience with resection and transplantation. Surgery 2010;148:778-782 discussion 782-4.

- 13. Tagge EP, Tagge DU, Reyes J, Tzakis A, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE, et al. Resection, including transplantation, for hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma: impact on survival. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:292-296 discussion 297.

- 14. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-699.

- 15. Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 2001;33:1394-1403.

- 16. Leung JY, Zhu AX, Gordon FD, Pratt DS, Mithoefer A, Garrigan K, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a multicenter study. Liver Transpl 2004;10:1343-1354.

- 17. Ismail H, Broniszczak D, Kaliciński P, Markiewicz-Kijewska M, Teisseyre J, Stefanowicz M, et al. Liver transplantation in children with hepatocellular carcinoma. Do Milan criteria apply to pediatric patients? Pediatr Transplant 2009;13:682-692.

- 18. McAteer JP, Goldin AB, Healey PJ, Gow KW. Surgical treatment of primary liver tumors in children: outcomes analysis of resection and transplantation in the SEER database. Pediatr Transplant 2013;17:744-750.

- 19. Romano F, Stroppa P, Bravi M, Casotti V, Lucianetti A, Guizzetti M, et al. Favorable outcome of primary liver transplantation in children with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pediatr Transplant 2011;15:573-579.

- 20. McAteer JP, Goldin AB, Healey PJ, Gow KW. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: epidemiology and the impact of regional lymphadenectomy on surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:2194-2201.

- 21. Chen JC, Chen CC, Chen WJ, Lai HS, Hung WT, Lee PH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: clinical review and comparison with adult cases. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:1350-1354.

- 22. Tatekawa Y, Asonuma K, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, Tanaka K. Liver transplantation for biliary atresia associated with malignant hepatic tumors. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36:436-439.

- 23. Brunati A, Feruzi Z, Sokal E, Smets F, Fervaille C, Gosseye S, et al. Early occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in biliary atresia treated by liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11:117-119.

- 24. Iida T, Zendejas IR, Kayler LK, Magliocca JF, Kim RD, Hemming AW, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a 10-month-old biliary atresia child. Pediatr Transplant 2009;13:1048-1049.

- 25. Kim JM, Lee SK, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Choe YH, Park CK. Hepatocellular carcinoma in an infant with biliary atresia younger than 1 year. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:819-821.

Table 1Patient Characteristics (n=16)

Table 2Non-Surgical Cases

Table 3Non-Transplantation Surgical Cases

Table 4Liver Transplantation