Department of Surgery, University of Ulsan College of Medicine and Department of Pediatric Surgery, Asan Medical Center Children's Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Copyright © 2017 Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

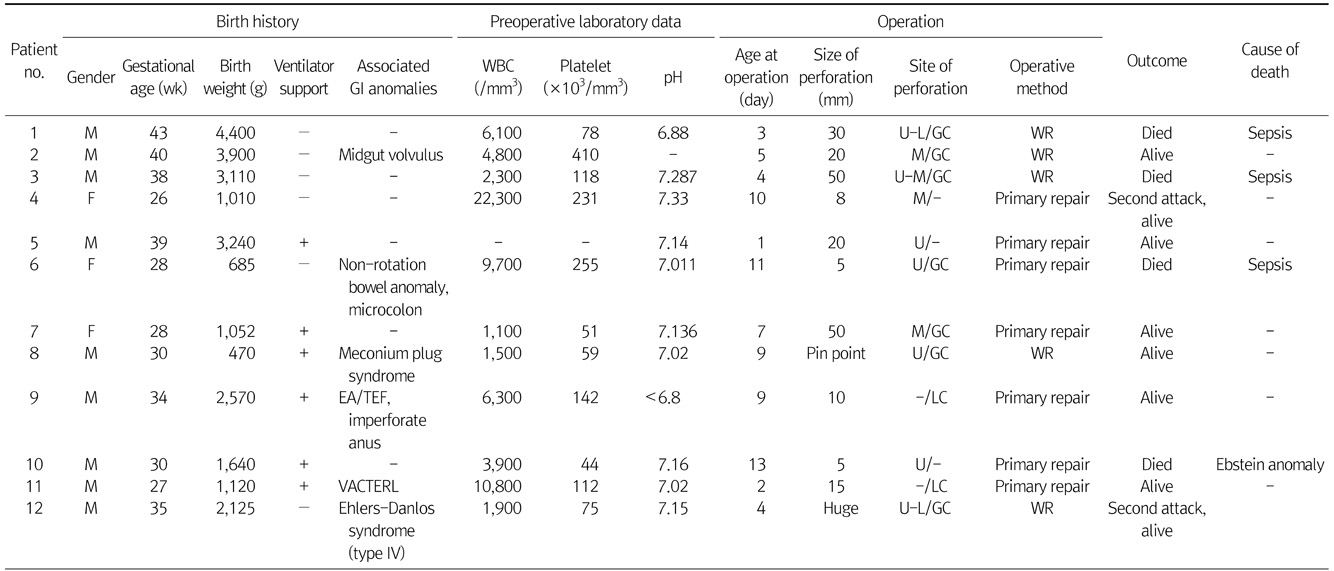

M, male (gender); F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; EA/TEF, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula; VACTERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, congenital heart disease, tracheoesophageal fistula or esophageal atresia, reno-urinary anomalies, and limb defect; U, upper stomach; M, middle stomach; L, lower stomach; GC, greater curvature; LC, lesser curvature; WR, wedge resection.

M, male (gender); F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; EA/TEF, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula; VACTERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, congenital heart disease, tracheoesophageal fistula or esophageal atresia, reno-urinary anomalies, and limb defect; U, upper stomach; M, middle stomach; L, lower stomach; GC, greater curvature; LC, lesser curvature; WR, wedge resection.

Values are presented as n (%).

WBC, white blood cell; GI, gastrointestinal; EA/TEF, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula.

a)Mortality and morbidity.

M, male (gender); F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; EA/TEF, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula; VACTERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, congenital heart disease, tracheoesophageal fistula or esophageal atresia, reno-urinary anomalies, and limb defect; U, upper stomach; M, middle stomach; L, lower stomach; GC, greater curvature; LC, lesser curvature; WR, wedge resection.

Values are presented as n (%).

WBC, white blood cell; GI, gastrointestinal; EA/TEF, esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula.

a)Mortality and morbidity.