ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

The establishment of enteral feeding is the end point of any intestinal anastomosis. This study examined the effects of early feeding (EF) as compared to delayed feeding (DF) on postoperative outcomes after intestinal anastomosis in children.

-

Methods

This was a randomized controlled pilot study to assess the effect of EF vs. DF in terms of time to reach full feed, along with wound infection and anastomotic leak.

-

Results

Twenty-eight patients were enrolled in both study groups. The median time to first feed in EF was 60 hours and 96 hours in DF. The median time to first bowel sound was 42 hours in EF and 48 hours in DF (p=0.208). The median time to first bowel movement was 72 hours in EF and 72 in DF (p=0.820). The median time of postoperative hospital stay was 5.5 days in EF and 6.0 days in DF (p=0.01). There was no significant difference in complications of wound infection, wound dehiscence, relook surgery, or anastomotic leak in both groups.

-

Conclusion

EF after intestinal anastomosis is safe and feasible in children after intestinal anastomosis.

-

Keywords: Early feeding; Intestinal anastomosis; Stoma closure; Enteral feeding

INTRODUCTION

Early postoperative enteral feeding after any gastrointestinal (GI) surgery has been a matter of debate for many years. The conventional belief is to withhold enteral feeding for a few days after any GI surgery involving anastomosis [

1]. This concept has been challenged by many authors where early postoperative feeding has been shown to be beneficial for early recovery of patients without any major complications [

1,

2]. While many studies have been done to prove the beneficial effect of early postoperative feeding in adults, there is a paucity of literature on this in children.

Early feeding (EF) is important in the pediatric age group as children tend to tolerate starvation poorly as compared to adults. EF after surgery helps in gut maturation, improves healing and has a role in promoting immunity and facilitates early resolution of ileus [

3]. It also considerably decreases the length of hospital stay and promotes early recovery [

4]. Prolonged fasting status may require some form of parenteral nutrition which has its own share of complications and may be difficult to procure in resource-limited countries. EF is also associated with a reduction in infectious complications as there is less risk of bacterial translocation along with a decreased risk of sepsis [

4]. This is related to an overall decreased risk of sepsis-related multiple organ dysfunction and decreased postoperative mortality rate. Delayed feeding (DF) is associated adversely with postoperative recovery. Malnourished children are more predisposed to surgical complications and delaying feeds in them may add to the insult [

5]. In such children, DF may further hamper anastomotic healing. We studied the safety and feasibility of early enteral feeds in children.

METHODS

This was a pilot randomized controlled observation study in children undergoing intestinal anastomosis in a tertiary care teaching hospital in India from January 2019 to December 2019. Patients were enrolled in the study after clearance from Institute Ethics Committee of the post graduate institute of medical education and research Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Chandigarh (IEC No. 2019/000388) and informed parental consent and assent in children above 7 years. Block randomization was used to divide the groups. Inclusion criteria was patient below 12 years’ age with single anastomosis below the ligament of Treitz. Patients undergoing hepaticojejunostomy were included in the study to assess the jejunojejunal anastomosis. Exclusion criteria were patients on inotropic support, those undergoing surgery for neonatal intestinal atresia’s, Duhamel’s pull through, those who underwent multiple intestinal anastomosis and patients on steroids or medical condition like autoimmune diseases or cystic fibrosis. Patients were divided into two groups by block randomization, at the time of enrollment in the study.

Groups A included patient in whom EF was started within 1st 48 hours of surgery via nasogastric tube/orally. Feed was started in the form of clear liquids followed by milk feeds. Feeding was started at the rate of 1–2 mL/kg two hourly and was gradually increased if tolerated for 2 feeds by 1 mL/kg. Nasogastric tube feeding was gradually increased and oral feed was started when tolerated. Full feed was considered established if child was tolerating at least 80% of maintenance fluid volume as feed. Any patients who manifested abdominal distension/vomiting/high post feed aspirate, 2 feeds were withheld and feeding restarted after 4–6 hours.

Groups B included patients in whom postoperative feeding was started as per conventional timing. This standard group (SG) is taken as DF group. These patients were kept nil per oral till the 5th postoperative day or passage of stool and flatus and decrease of nasogastric aspirates.

Patients in both groups underwent total gut irrigation in the form of normal saline wash through nasogastric tube preoperatively. The flow rate was set 25 mL/kg/hour and increased to up to 40 ml/kg/hour for a total of 4–5 hours or till effluents were clear (whichever was earlier). All patients planned for restoration of bowel continuity underwent distal stoma washes 4 hourly with normal saline 25 mL/kg/hour. All patients underwent intestinal anastomosis with Vicryl® (Polyglactin 910) 4-0/5-0, in single layer interrupted manner. Preoperatively antibiotic were given half an hour before skin incision. All patients received adequate preoperative and postoperative fluids and analgesia as per standard protocol. Preoperatively complete blood count, serum electrolytes, renal function test, growth percentiles (height, weight) and body mass index of patient were recorded. In the postoperative period time to first feed in hours, time to full feed in hours, nasogastric tube reinsertion and intolerance of feed, any electrolyte imbalance, time to first bowel movement, time to appearance of bowel sounds, time to discharge, complication if any like surgical site infections (SSI), wound dehiscence, anastomotic leak, intraabdominal collection, vomiting and abdominal distension were noted. All patients were monitored for signs of anastomotic leak like tachycardia, fever, abdominal tenderness and clinical worsening condition of child. Relevant investigations like ultrasound abdomen and CBC along with X-rays were carried out to diagnose any anastomotic leak. Those patients who had anastomotic leak were exited from the study and managed as per departmental protocols. Patients were followed in postoperative period during their stay in the hospital and at 30 days for SSI.

RESULTS

Overall, 16 patients (13 in EF and 3 in SG) were females (28%) while 40 (15 in EF and 25 in SG) were males (72%). Mean age in the EF group was 4.19 years while it was 4.03 years in SG group (p=0.853). Mean weight was 13.09 kg in EF group while it was 12.79 kg in SG group (p=0.834) (

Table 1).

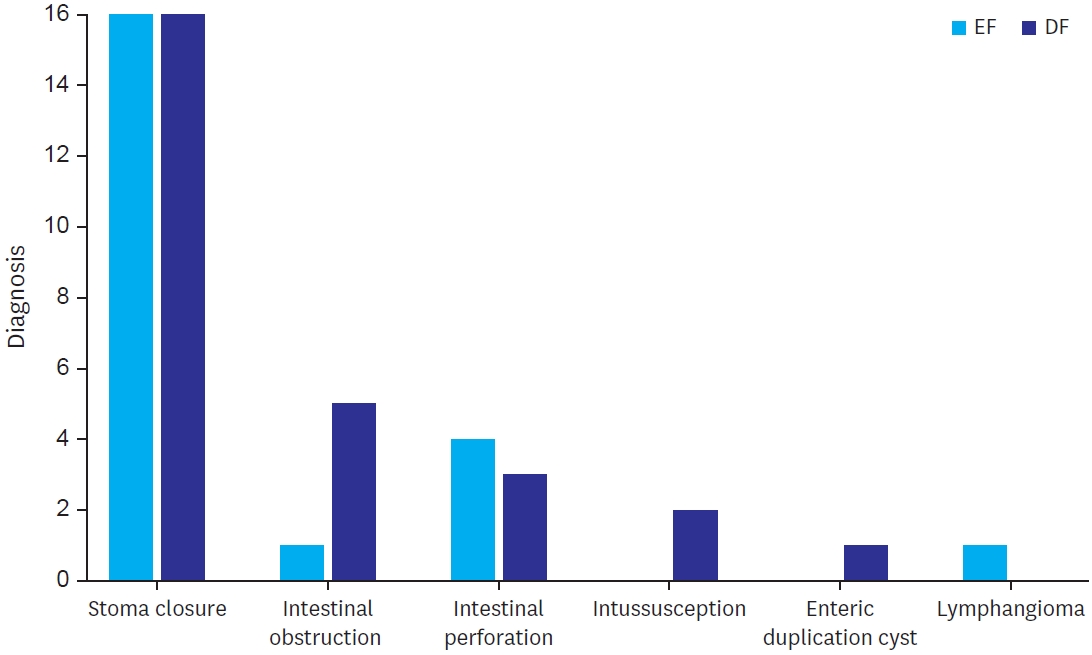

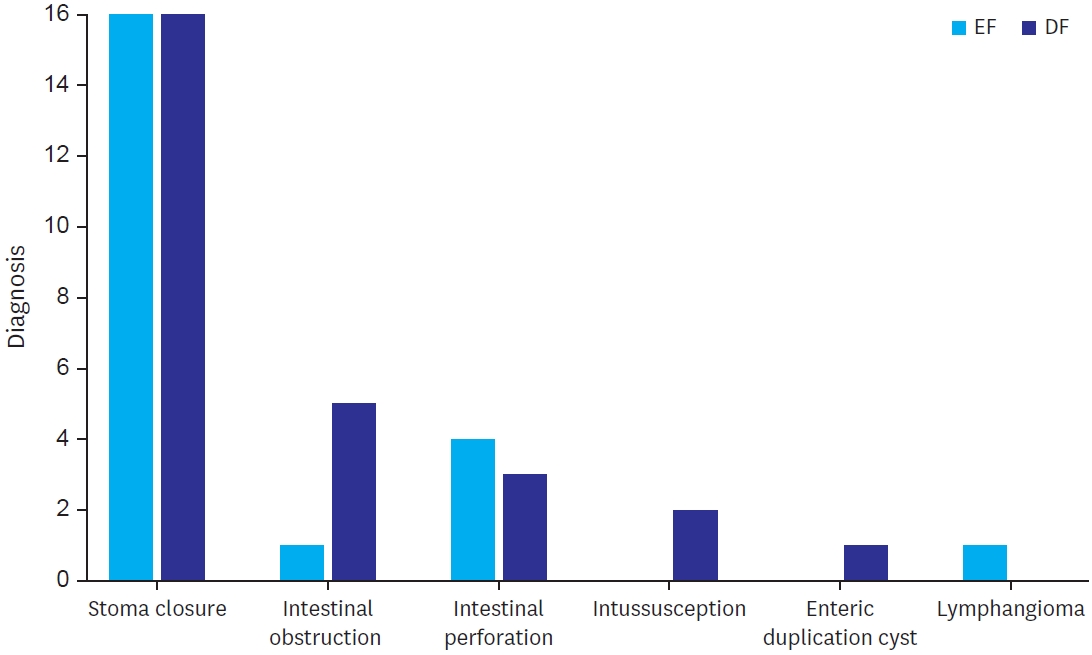

Majority of the cases were restoration of bowel continuity after creation of stoma (57% of the cases in both the group). Stoma closure was done after high divided sigmoid colostomy in 23 patients (41%), after ileostomy in 10 patients (17%) and in 1 case after diversion colostomy done for perineal injury. Emergency surgeries included intestinal obstruction including Meckel’s band obstruction (1 case in EF and 5 cases in DF), perforation (4 cases in EF and 3 cases in SG) and intussusception (no case in EF and 2 cases in SG) (

Fig. 1).

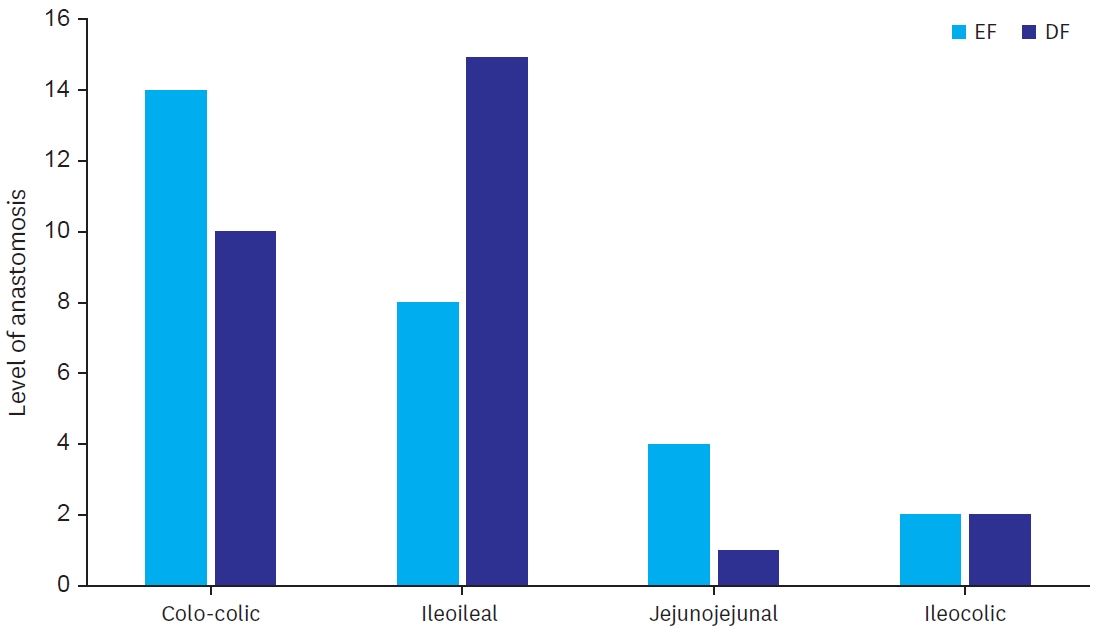

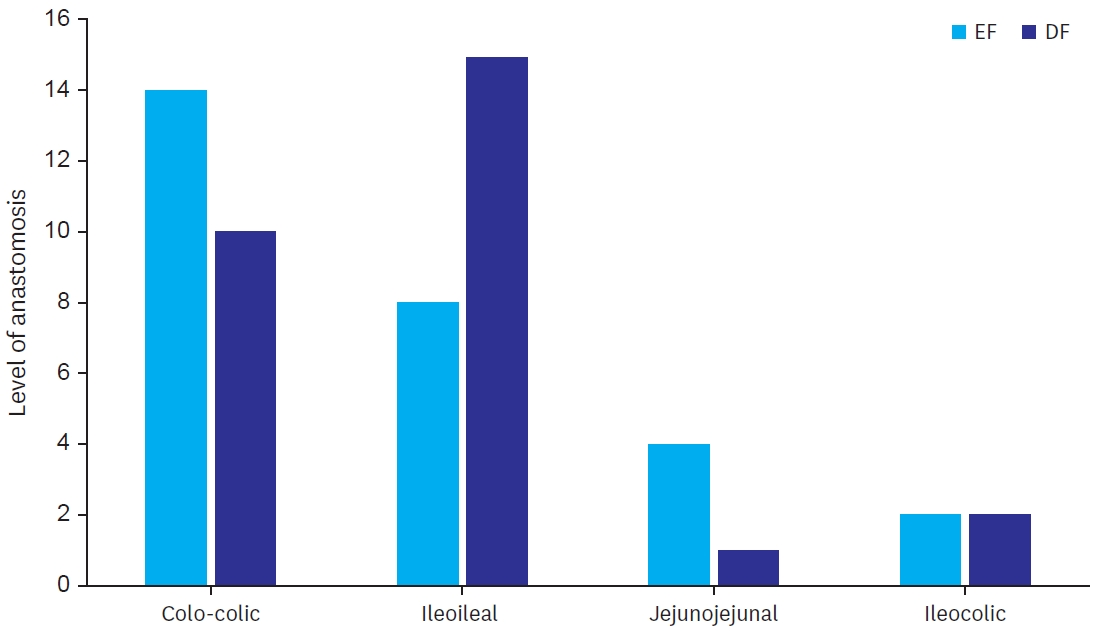

Level of anastomosis were colo-colic (14 in EF and 10 in SG), ileocolic (2 in EF and 2 in SG, jejunojejunal (4 in EF and 1 in SG) and ileoileal (8 in EF and 15 in SG) (

Fig. 2).

Median time to first feed in EF was 60 hours in EF and 96 hours in SG (p=0.00). Median time to first bowel sound was 42 hours in EF and 48 hours in SG (p=0.208). No patient in EF required reinsertion of nasogastric tube while 1 patient in SG required reinsertion of nasogastric tube (3.6% study group) (p=0.313). Median days of hospital stay in EF was 5.5 and SG was 6 (p=0.00) (

Table 2). There were no complications of wound infection, wound dehiscence, relook surgery or anastomotic leak in both the groups.

DISCUSSION

There are no clear guidelines which establish the timing of enteral feed in children after intestinal anastomosis. Although there is a plethora of relevant literature among adults validating the benefits of EF, few studies are available in children. Wound healing occurs in three stages—inflammatory stage where cytokines attract inflammatory cells, proliferative phases where macrophages affect fibroblastic activity and collagen deposition, and finally remodeling phase [

5]. Experimental studies have shown improved wound healing after intestinal anastomosis in cases of early enteral feeding even in presence of sepsis [

6].

EF is associated in maintaining gut integrity and prevents bacterial translocation across the gut. It in turn may aid in preventing postoperative sepsis [

7]. EF also helps in early resolution of postoperative ileus [

8]. EF also helps in early anastomotic healing [

9]. It facilitates wound healing by deposition of mature collagen at the anastomotic site [

10]. EF has shown favorable response in the terms of wound healing, shows positive nitrogen balance and improved sepsis resistance [

3]. It also ameliorates oxidative stress after surgery [

11]. In our study, number of complications in both EF and DF group were not significantly different. While there was one patient with reinsertion of nasogastric tube in DF, no such incidence was there in EF. This was, however, statistically insignificant. The mean time to full feed was significantly less in EF as compared to DF. Also, there was a significant difference in time of hospital stay. Length of hospital stay was less in EF group.

Most of the patients in our study were malnourished in preoperative period (62% patient having <5 percentile of weight for their age). In malnourished children, DF further hampers anastomotic healing. DF is also associated with prolonged postoperative ileus [

7]. Prolonged ileus increases morbidity like vomiting and abdominal distension and is associated with prolonged hospital stay and delayed recovery. In prolonged fasting after surgery, bacterial translocation across gut wall is increased leading to various septic complications. Also immunity decreases which leads to increased risk of various infections. Infective complications like SSI and wound dehiscence are more in patients undergoing delayed postoperative feeding.

Amanollahi and Azizi [

1] in their study on EF vs. DF after intestinal anastomosis have concluded that EF is safe and has fewer complications as compared to control. It was a randomized study where EF was started after 24 hours of surgery. In this study length of hospital stay and time to defecation were decreased while there was no major difference between the complications rate. In our study, favorable outcomes in terms of length of hospital stay, time to first feed and complication rates were seen, but feeding was started at mean of 59.71 hours as compared to previous studies like by Yadav et al. [

12], Ekingen et al. [

13] and Sangkhathat et al. [

14]. Yadav et al. [

12] in their study have started feeding 24 hours after surgery while Ekingen et al. [

13] demonstrated safety of oral feeding started within 24 hours after intestinal anastomosis. This study included neonates operated for various congenital anomalies. This study established the safety of EF in the neonatal population after intestinal anastomosis. Sangkhathat et al. [

14] demonstrated safety and benefit of early enteral feeding, started within 24 hours of surgery, in pediatric stoma closure in anorectal malformation patients compared to retrospective controls. Mamatha and Alladi [

15] demonstrated safety of early oral feeding, started within 24 hours, in pediatric intestinal anastomosis. While this was a nonrandomized study, outcome in terms of safety of EF and shorter length of hospital stay was similar to our study. In yet another study carried out by Yadav et al. [

12] in 2013 from India, pediatric patients under 12 years of age undergoing elective stoma closure were prospectively listed in EF group (started within first 24 hours of operation) and compared to retrospective controls in late feeding group. They demonstrated fewer complications in EF group along with significantly faster recovery. While outcome of the study is similar to the present study in terms of faster recovery, the present study was a prospective randomized study. Complications rates in the present study were similar in both EF and SG. In a study by Mo et al. [

16] early enteral nutrition was started by feeding jejunostomy in children after GI surgery. Compared to control group time to first flatus/stool was reduced, serum albumin and calcium levels were higher and body mass index increased significantly in early EF group. In the present study oral feeding was started instead of enteral feed via feeding jejunostomy. Serum albumin and calcium levels were not included in our study while time to first stool/flatus was not significantly different between EF and SG.

The study included more elective cases than emergency cases. Level of anastomosis were also varied (

Fig. 2). As it was a pilot study in our institute over a fixed period of time, sample size was small leading to small representative sample. For further validity of the results, large scale study with both emergency and elective cases needs to be carried out. The median timing of start of EF was 60 hours in our study. To validate the safety of EF future studies with EF started at less than 48 hours needs to be done.

NOTES

-

Presentation

Manuscript presented in IAPSCON 2020, India (virtual conference).

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Upreti S, Peters NJ, Samujh R; Data curation: Upreti S; Formal analysis: Upreti S; Funding acquisition: Peters NJ, Samujh R; Investigation: Upreti S, Peters NJ, Samjh R; Methodology: Upreti S, Peters NJ, Samujh R; Project administration: Upreti S, Peters NJ, Samujh R; Resources: Peters NJ, Samujh R; Software: Upreti S, Peters NJ; Supervision: Peters NJ, Samujh R; Validation: Peters NJ, Samujh R; Visualization: Peters NJ, Samujh R; Writing - original draft: Upreti S, Peters NJ; Writing - review & editing: Upreti S, Peters NJ, Samujh R.

Fig. 1.

Different diagnoses for which anastomosis was done.

EF, early feeding; DF, delayed feeding.

Fig. 2.

Levels of different anastomosis.

EF, early feeding; DF, delayed feeding.

Table 1.

Table 1.

|

Variables |

Study group |

No. |

Mean ± standard deviation |

p-value |

|

Age in years |

Early feeding |

28 |

4.19±3.413 |

0.853 |

|

Delayed feeding |

28 |

4.03±2.985 |

|

|

Weight |

Early feeding |

28 |

13.09±5.563 |

0.834 |

|

Delayed feeding |

28 |

12.79±4.921 |

|

Table 2.Postoperative parameters and outcome

Table 2.

|

Variables |

Group |

Median |

IQR |

p-value |

|

Time to first feed (hr) |

Early feeding |

60.00 |

18 |

0.000 |

|

Delayed feeding |

96.00 |

20 |

|

|

Time to full reached feed (hr) |

Early feeding |

110.00 |

20 |

0.000 |

|

Delayed feeding |

130.00 |

30 |

|

|

Time to first bowel movement (hr) |

Early feeding |

72.00 |

2 |

0.820 |

|

Delayed feeding |

72.00 |

2 |

|

|

Time to first bowel sound (hr) |

Early feeding |

42.00 |

12 |

0.208 |

|

Delayed feeding |

48.00 |

12 |

|

|

Time to nasogastric tube removal (hr) |

Early feeding |

60.00 |

12 |

0.000 |

|

Delayed feeding |

96.00 |

25 |

|

|

Time till IVF stopped (hr) |

Early feeding |

110.00 |

28 |

0.000 |

|

Delayed feeding |

130.00 |

30 |

|

|

Postoperative stay (days) |

Early feeding |

5.50 |

1 |

0.001 |

|

Delayed feeding |

6.00 |

1 |

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Amanollahi O, Azizi B. The comparative study of the outcomes of early and late oral feeding in intestinal anastomosis surgeries in children. Afr J Paediatr Surg 2013;10:74-7.

- 2. Klappenbach RF, Yazyi FJ, Alonso Quintas F, Horna ME, Alvarez Rodríguez J, Oría A. Early oral feeding versus traditional postoperative care after abdominal emergency surgery: a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2013;37:2293-9.

- 3. Dervenis C, Avgerinos C, Lytras D, Delis S. Benefits and limitations of enteral nutrition in the early postoperative period. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2003;387:441-9.

- 4. Shang Q, Geng Q, Zhang X, Xu H, Guo C. The impact of early enteral nutrition on pediatric patients undergoing gastrointestinal anastomosis a propensity score matching analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0045.

- 5. Williams NS, O’Connell PR, McCaskie AW. Bailey and Love's short practice of surgery. 27th ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2018.

- 6. Kiyama T, Onda M, Tokunaga A, Yoshiyuki T, Barbul A. Effect of early postoperative feeding on the healing of colonic anastomoses in the presence of intra-abdominal sepsis in rats. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:S54-8.

- 7. Kudsk KA. Importance of enteral feeding in maintaining gut integrity. Tech Gastroint Endosc 2001;3:2-8.

- 8. Boelens PG, Heesakkers FF, Luyer MD, van Barneveld KW, de Hingh IH, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, et al. Reduction of postoperative ileus by early enteral nutrition in patients undergoing major rectal surgery: prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 2014;259:649-55.

- 9. Moss G, Greenstein A, Levy S, Bierenbaum A. Maintenance of GI function after bowel surgery and immediate enteral full nutrition. I. Doubling of canine colorectal anastomotic bursting pressure and intestinal wound mature collagen content. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1980;4:535-8.

- 10. Schroeder D, Gillanders L, Mahr K, Hill GL. Effects of immediate postoperative enteral nutrition on body composition, muscle function, and wound healing. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1991;15:376-83.

- 11. Kotzampassi K, Kolios G, Manousou P, Kazamias P, Paramythiotis D, Papavramidis TS, et al. Oxidative stress due to anesthesia and surgical trauma: importance of early enteral nutrition. Mol Nutr Food Res 2009;53:770-9.

- 12. Yadav PS, Choudhury SR, Grover JK, Gupta A, Chadha R, Sigalet DL. Early feeding in pediatric patients following stoma closure in a resource limited environment. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:977-82.

- 13. Ekingen G, Ceran C, Guvenc BH, Tuzlaci A, Kahraman H. Early enteral feeding in newborn surgical patients. Nutrition 2005;21:142-6.

- 14. Sangkhathat S, Patrapinyokul S, Tadyathikom K. Early enteral feeding after closure of colostomy in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg 2003;38:1516-9.

- 15. Mamatha B, Alladi A. Early oral feeding in pediatric intestinal anastomosis. Indian J Surg 2015;77:670-2.

- 16. Mo Z, Yan L, Zhang W, He H, Huang S, Yang W. Effects of early enteral nutrition on gastrointestinal function recovery and nutrition status after gastrointestinal surgery in children. Dig Med Res 2019;2:14.