ABSTRACT

Intestinal failure (IF) is a term used to define the state where intestine’s function is significantly reduced, to the point where adequate growth and hydration cannot be maintained. In such cases, intravenous nutritional support is essential for sustaining the patient’s life. In pediatric patients, the most common cause of IF is short bowel syndrome (SBS). Due to the prolonged treatment and high complication rates, management of SBS remains a continuous challenge to many physicians. Herein, we report the case of a 2,260 g premature female infant born at 35-week gestational age with type 4 jejunoileal atresia. She presented with ultrashort bowel syndrome, having a bowel length of less than 15 cm, but ultimately achieved gut autonomy and restored bowel function through successful intestinal rehabilitation within the first two years of life.

-

Keywords: Intestinal failure; Intestinal atresia; Short bowel syndrome; Nutritional support

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal failure refers to various conditions where the gut is unable to absorb sufficient fluid, nutrients and electrolyte. The reduced functional gut mass, resulting from either anatomical or functional impairment, hinders proper growth and survival [

1].

In children, the major causes include motility disorders such as pseudo-obstruction, necrotizing enterocolitis, mucosal enteropathy, and congenital anomalies including intestinal atresia and volvulus [

2]. Among all, short bowel syndrome (SBS) followed by extensive bowel resection is known as the most common cause, with an estimated incidence of 24.5 per 100,000 live births [

3].

It is difficult to define the exact length of the small intestine that would lead to SBS in pediatric patients, as it varies with age and weight. However, generally, a residual small bowel length of 10–20 cm or less than 10% of the expected length of age is classified as an “ultrashort bowel syndrome (USBS)” [

3,

4]. Management of USBS in pediatric patients is a complex and multifaceted challenge, as they often require prolonged, open-ended parenteral nutrition. According to recent data from 2017, the mortality rate for USBS patients has been reported to be approximately 47% [

3]. At our institution, we have accumulated over 20 years of experience in successfully treating both pediatric and adult SBS patients. We report a successful case of intestinal rehabilitation in a premature infant with USBS, having a bowel length of about 15 cm.

CASE REPORT

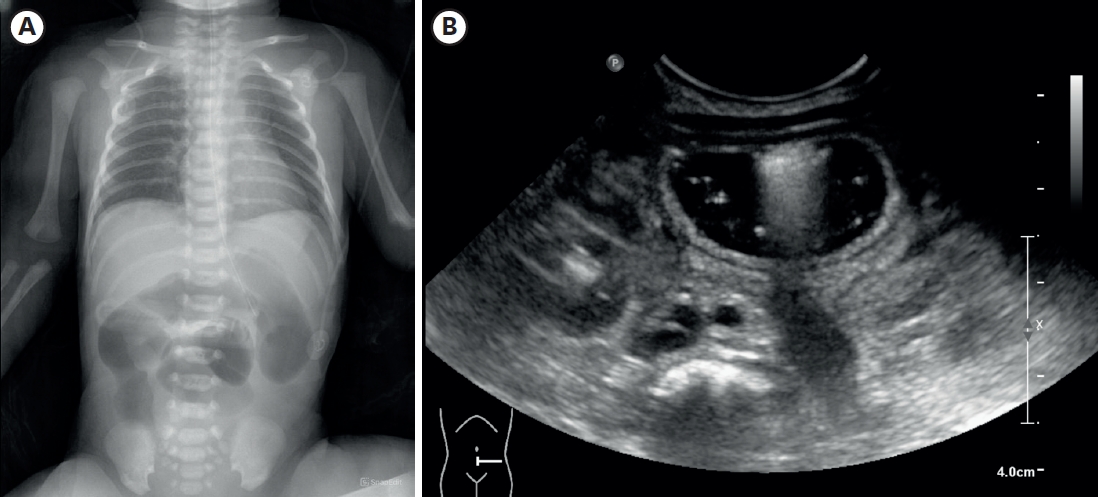

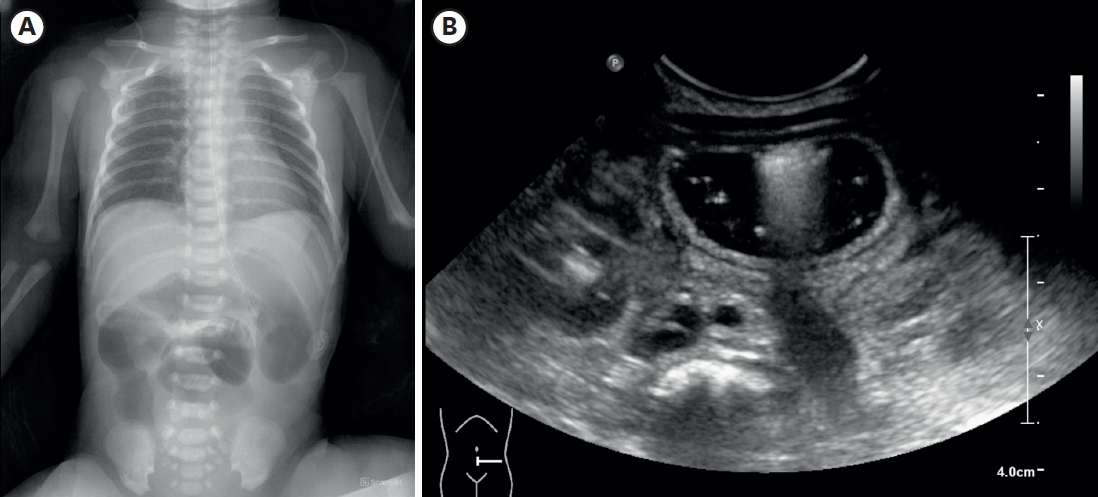

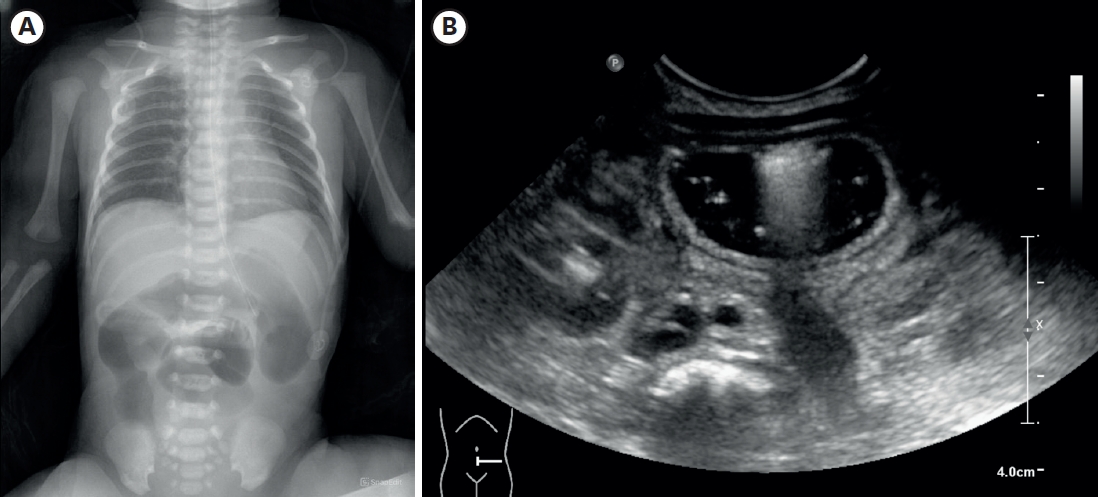

A female infant was born as a twin 1st baby via cesarean section at 35+2 weeks gestation, weighing 2,260 g. Her 38-year-old mother had a history of gestational diabetes, and experienced premature membrane rupture during referral to our hospital. The prenatal ultrasound showed fetal bowel dilatation suggesting small bowel obstruction. Gastric tube drainage was bile-stained, and the abdomen was mildly distended, but not tense. Infantogram showed several distended proximal small bowel loops, with nonvisible rectal gas (

Fig. 1A). On the postnatal ultrasound, the rectum and distal sigmoid were all collapsed, with no signs of malrotation or midgut volvulus (

Fig. 1B). There was no family history of malformation, and aside from a small atrial septal defect detected on echocardiography, she had no other anomalies.

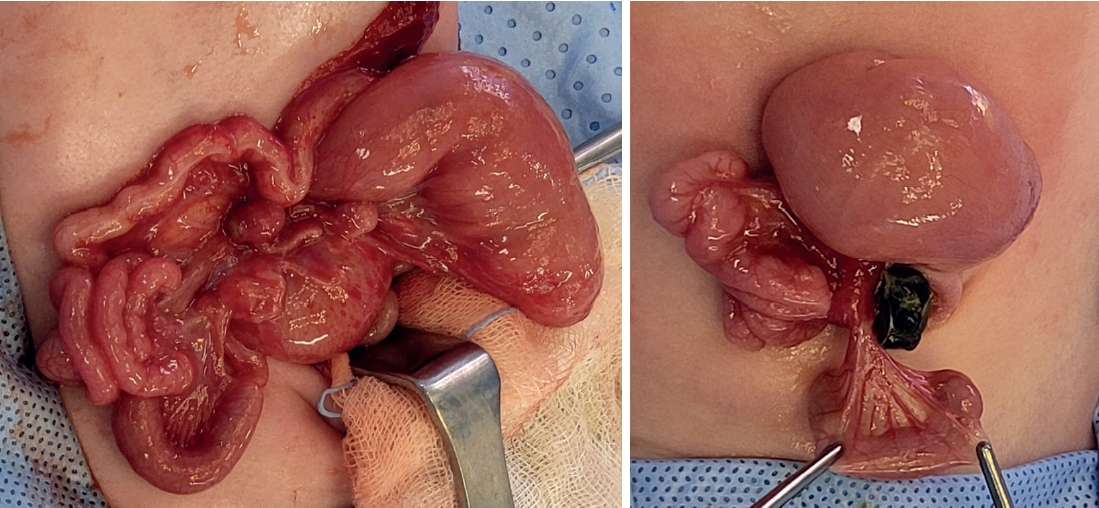

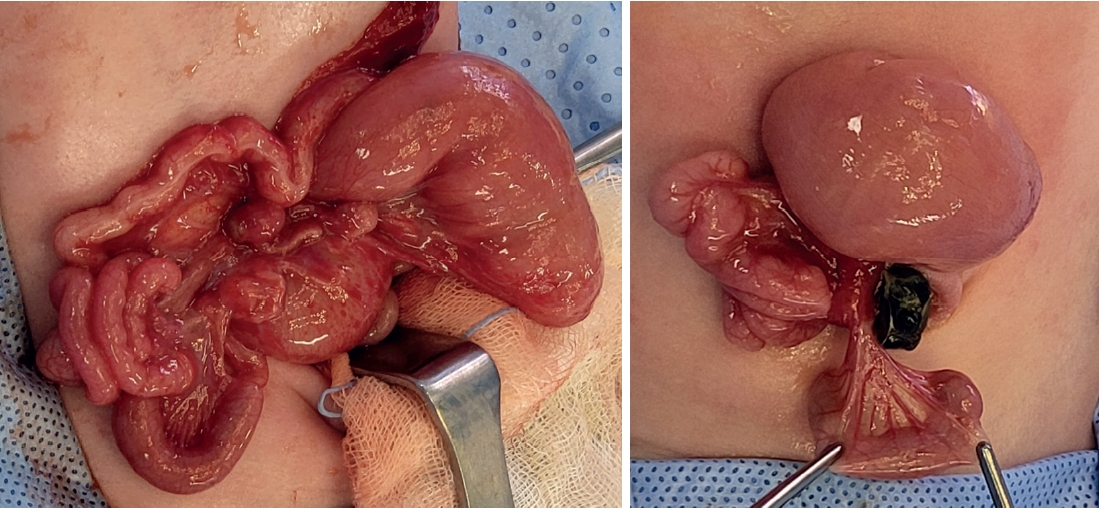

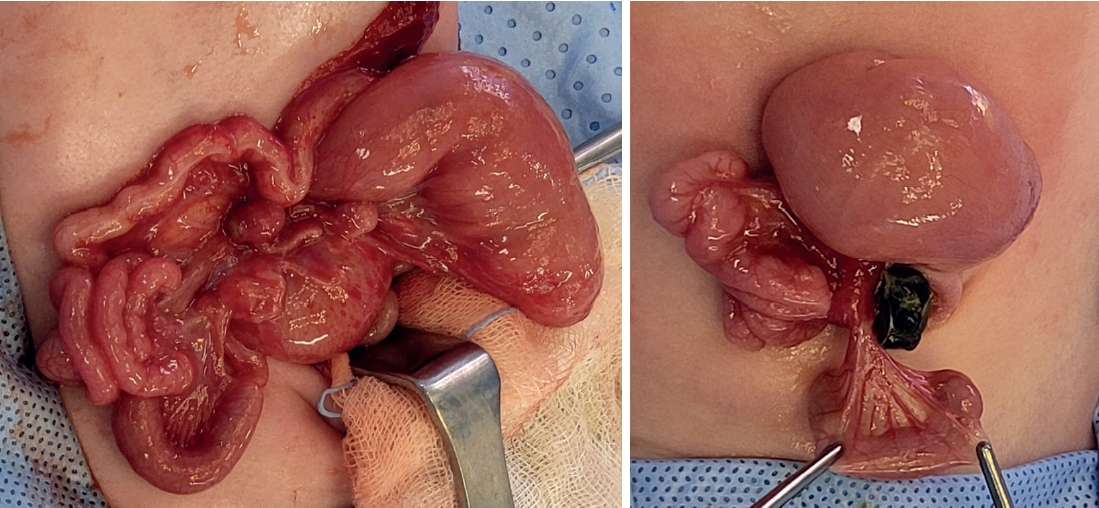

On the second day after birth, the patient underwent emergency surgery and diagnosed with jejunoileal atresia type IV (

Fig. 2). From 7 cm below the Treitz ligament, the entire small intestine was found to be atretic, necessitating an en-bloc resection and a single anastomosis. The anastomosis was performed in an end-to-end fashion, as enteroplasty was not feasible due to limited length of proximal bowel. Ultimately, the remaining small intestine measured a total length of 15 cm, including up to 8 cm above the IC valve.

Post-operative day 14, the patient started intermittently feeding elemental formula (Neocate

®, Nutricia Ltd, Wiltshire, UK) via orogastric tube. This is an amino acid-based formula, accounting 71 kcal per 100 mL, mainly used in the care of children with feeding difficulties due to food allergies or intestinal malabsorption. Initial enteral feeding commenced at 5 mL every 3 hours, with planned incremental increases of approximately 5 mL each time. However, due to persistent radiographic evidence of gastric and duodenal distension, an upper gastrointestinal series was performed on postoperative day 12, which revealed passage delay at the anastomosis site, necessitating a more conservative approach for feeding advancement. For approximately one month, enteral feeding was maintained at 10 mL every 3 hours without further increases. By day 40, clinical improvement allowed for gradual volume increases of 3–5 mL per feeding daily, and at day 60, with decreased gastric aspirate output, the orogastric tube was removed. Subsequently, as oral intake increased, the patient developed diarrhea (about 10–20 g/kg/day, 3–5 times/day), which led to additional one-month period of adjustment, with a concurrent reduction in enteral feeding and increase in intravenous nutrition (total parenteral nutrition [TPN]). After stool condition stabilized, feeding volume was modified on a weekly basis, and after 7 weeks of gradual advancement, oral intake reached approximately 80 kcal/kg/day (

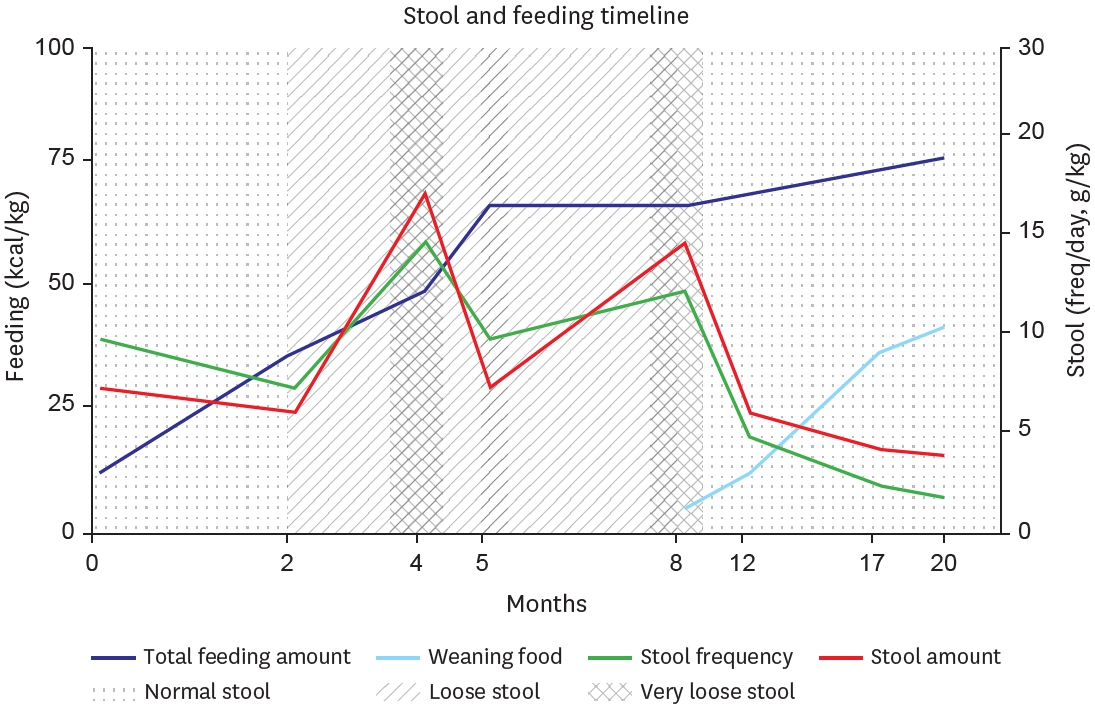

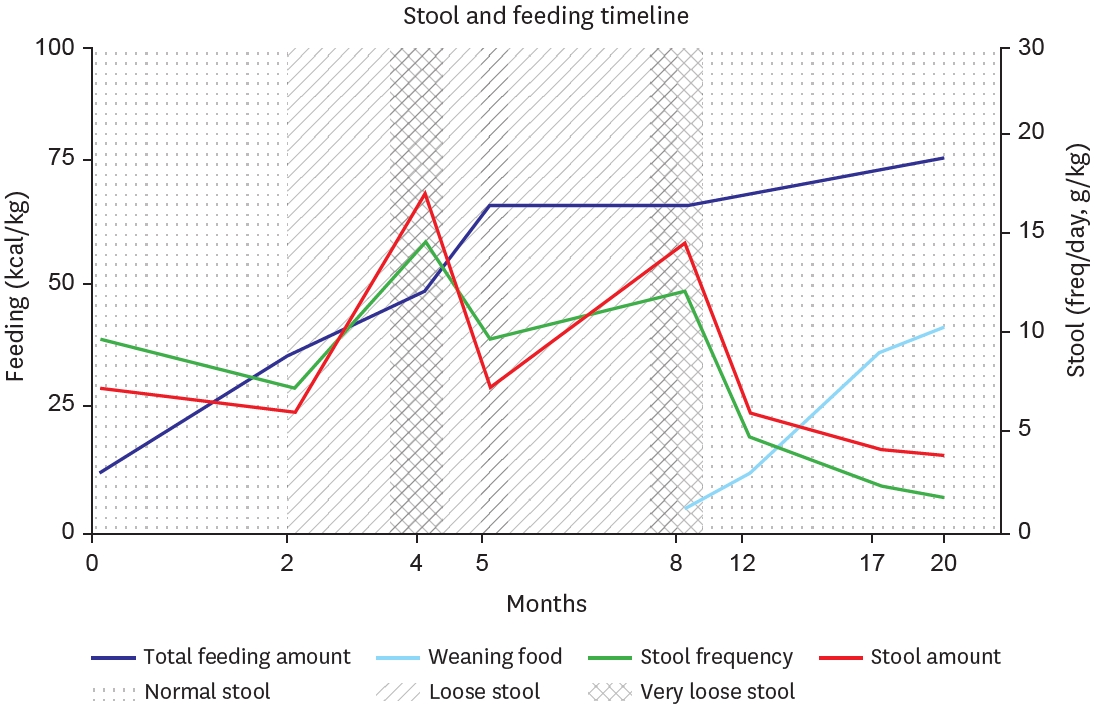

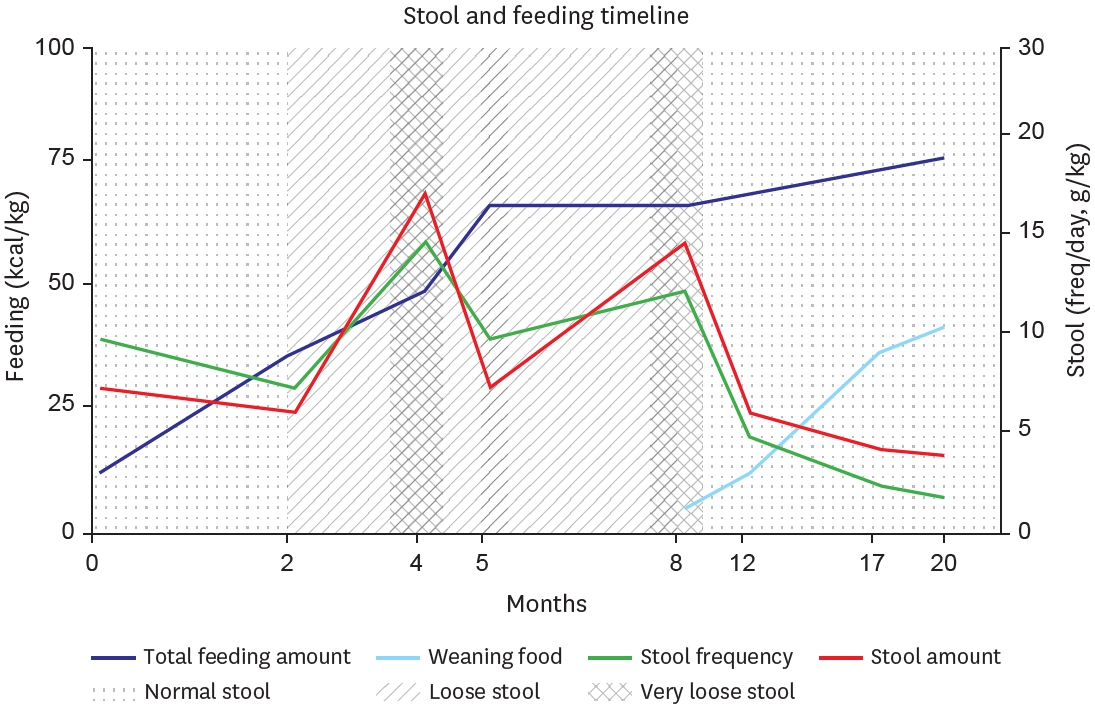

Fig. 3).

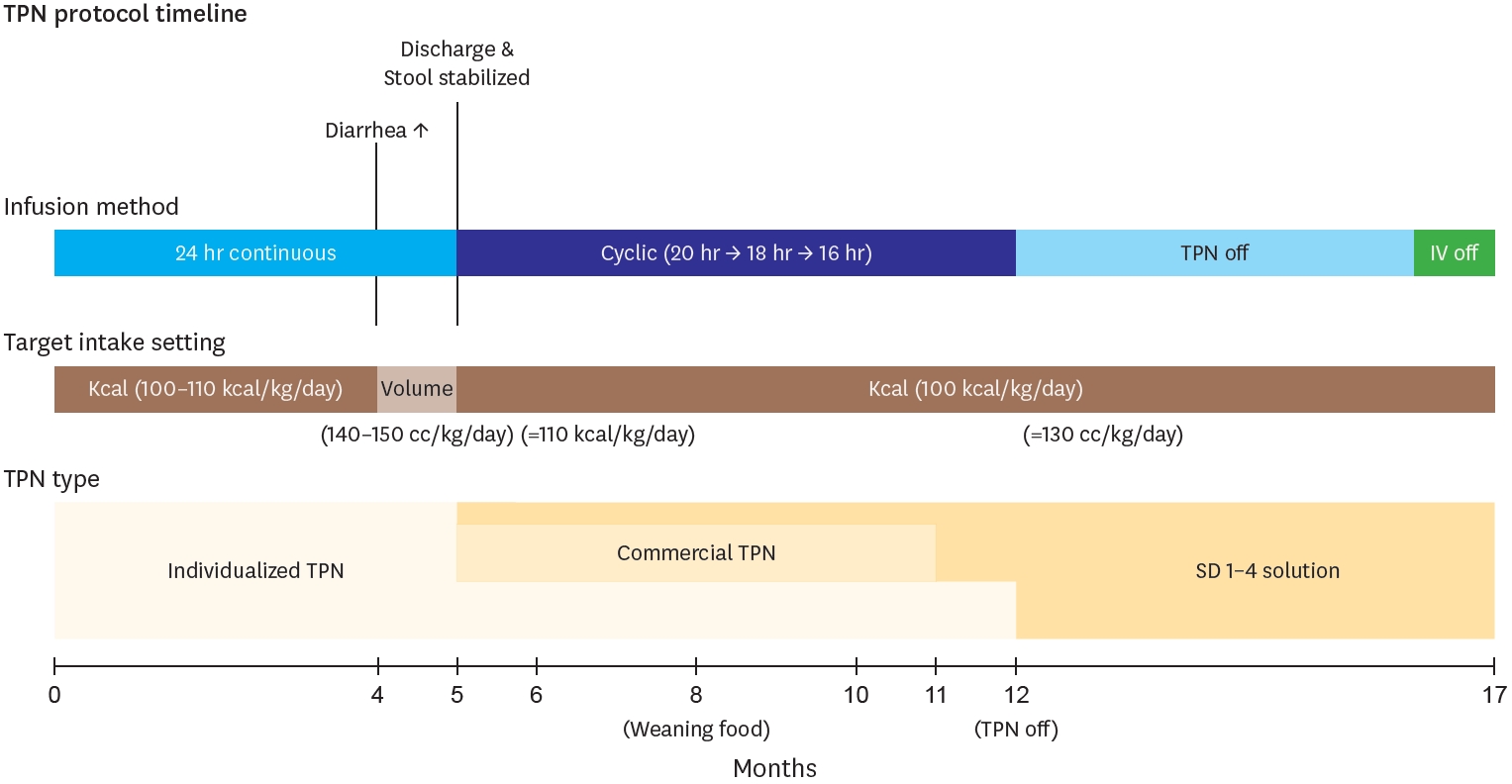

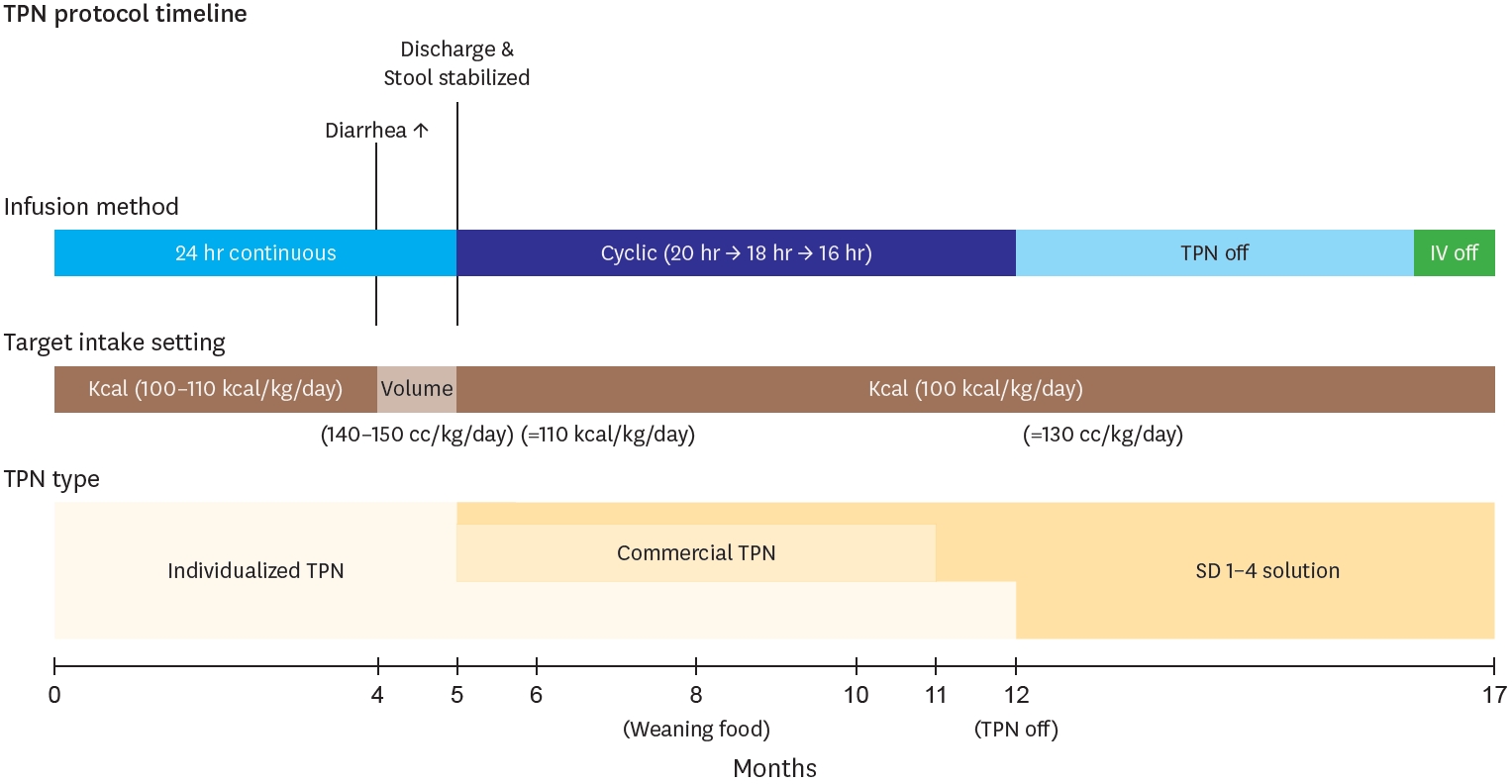

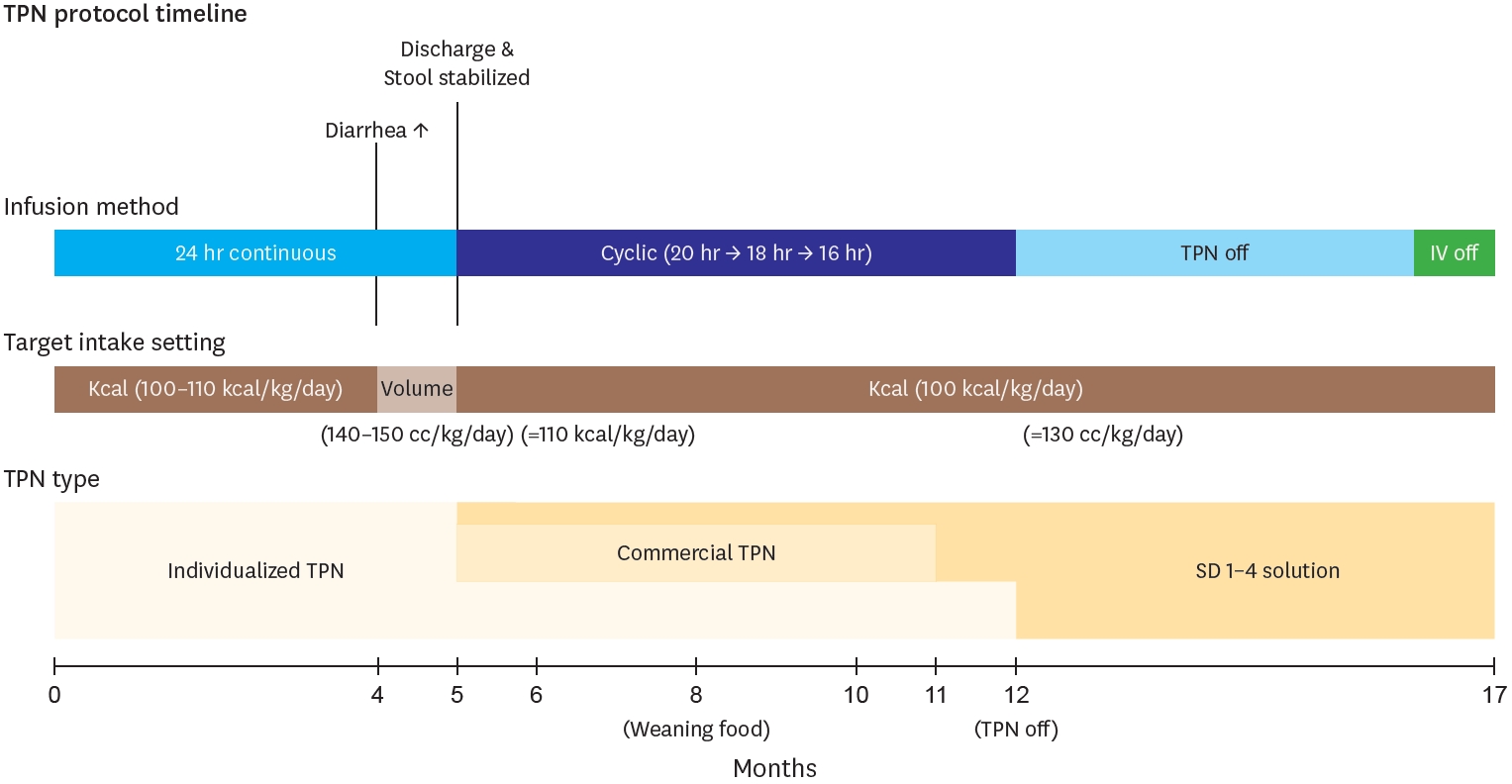

Considering the intake, total calories were calculated according to European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines [

5], and supplied targeting 100–130 kcal per kg per day. Calories excluding enteral feeding were provided through an individualized TPN compound. This TPN contains 0.89 kcal/mL, and its maximum administration was gradually adjusted according to the following parameters: glucose infusion rate of 10–14 mg/kg/min, protein 2.5–3 g/kg/day, and lipids 2.5–3 g/kg/day. Around 4 months of age, when diarrhea frequency increased, the nutritional target was adjusted based on total volume rather than caloric intake, maintaining 140–150 mL/kg/day to prevent dehydration. During this period, total caloric intake averaged 110 kcal/kg/day. After stool patterns stabilized and oral intake consistently exceeded 80 kcal/kg/day, the nutritional strategy was shifted back to a calorie-based target, with constant TPN supplementation for any caloric deficits. Under this approach, the average fluid intake was maintained at approximately 130 mL/kg/day. During the five-month hospitalization period, TPN was primarily administered via continuous infusion, and transitioned to a cyclic course by the time of the discharge, starting at 20 hours and finally reduced to 16 hours. After discharge, considering the patients’ long distance to the hospital, the prescribed TPN was switched to commercial TPN with extended stability (Smofkabiven

® Central 986 mL, Fresenius Kabi Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea; Winuf

® Peripheral, JW Life Science, Dangjin, Korea) and SD 1–4 solution. Then at 12 months, TPN was tapered out, and at 17 months, all IV fluids were discontinued (

Fig. 4). Troughout the entire period, there no significant line complications, including infections, occurred. The only exception was one event when the Broviac catheter ruptured at 5.5 months and had to be changed due to injury. Central line management during home cyclic TPN included daily heparin locks (2–3 mL of 100 IU/mL solution) for obstruction prevention. Dressing changes were performed three times weekly using chlorhexidine, and the catheter insertion site was covered with a sterile transparent dressing to maintain aseptic conditions.

Regarding micronutrient supplementation, weekly vitamin K (1 mg) was administered, while other multivitamins and trace elements were mixed into the TPN according to ESPEN requirements. For pharmaceutical management, intravenous H2 blockers were maintained only during the initial fasting period, and antimotility drugs were not utilized. At 4 months of age, the patient demonstrated an acute elevation in liver enzymes (aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase 269/460 U/L), presumably due to prolonged TPN usage. A combination of ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg/day) and cholestyramine (9 g/day) was administered during the period, and after one week, all laboratory results normalized. The patient is currently maintaining only on probiotics (Lactobacillus reuteri, BioGaia®, Stockholm, Sweden) and Ursodeoxycholic acid.

At 8 months of age, the patient started feeding baby food, from rice porridge once daily, gradually progressing to include meat products. By 15 months of age, the patient began consuming diverse ingredients such as fish and fruits. At first, stool output was significant, exceeding 8 episodes per day with volumes up to 15 g/kg, so we titrated fish and meat portions in meal preparation. Subsequently, stool condition stabilized to 2–4 episodes daily with volumes of 6–7 g/kg. At 17 months of age, when parenteral fluids were discontinued, the patient was maintaining 80 kcal/kg or more through weaning foods and elemental formula. After 20 months of age, the patient progressed to consuming baby snacks, bread, and age-appropriate solid foods, while maintaining normal stool characteristics (

Fig. 3).

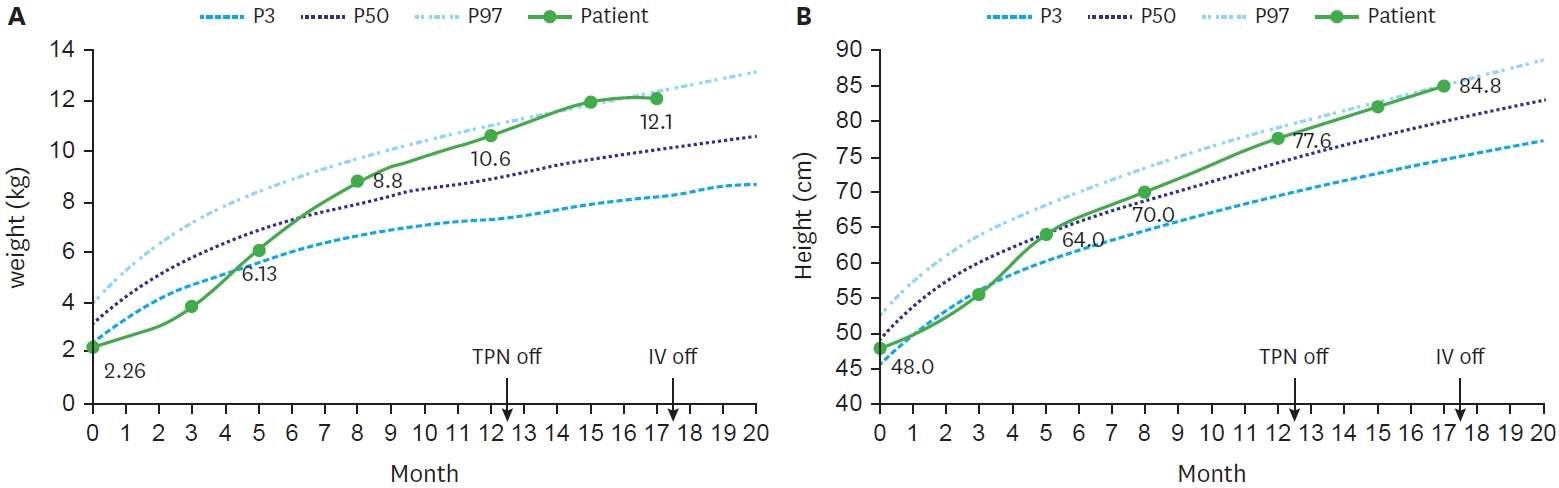

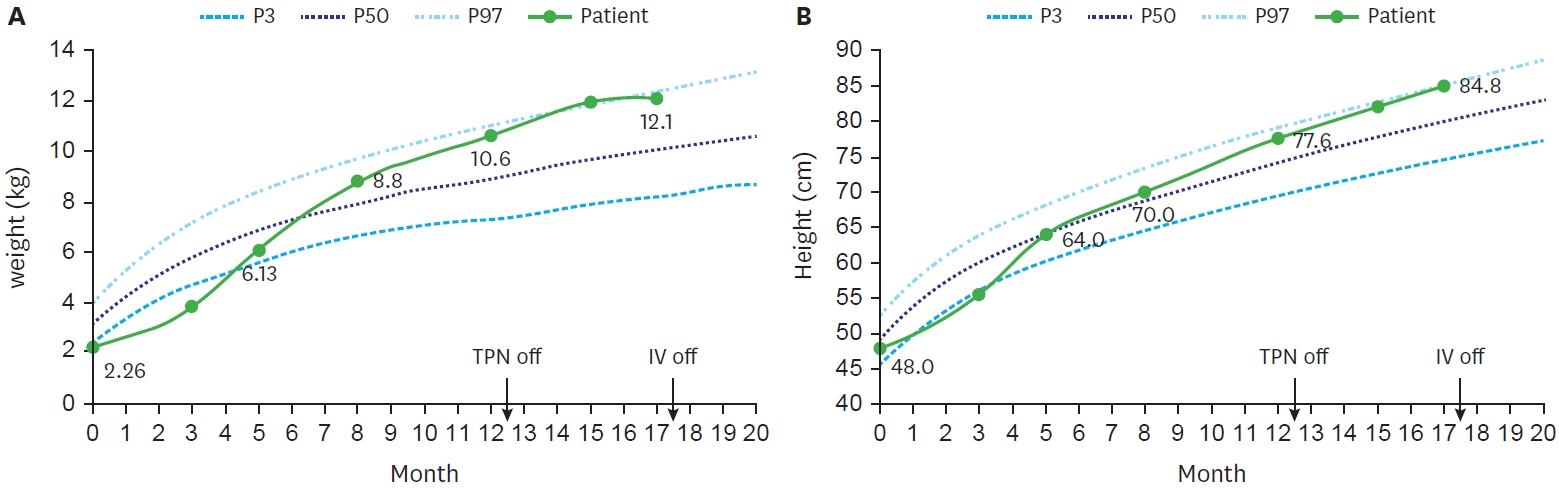

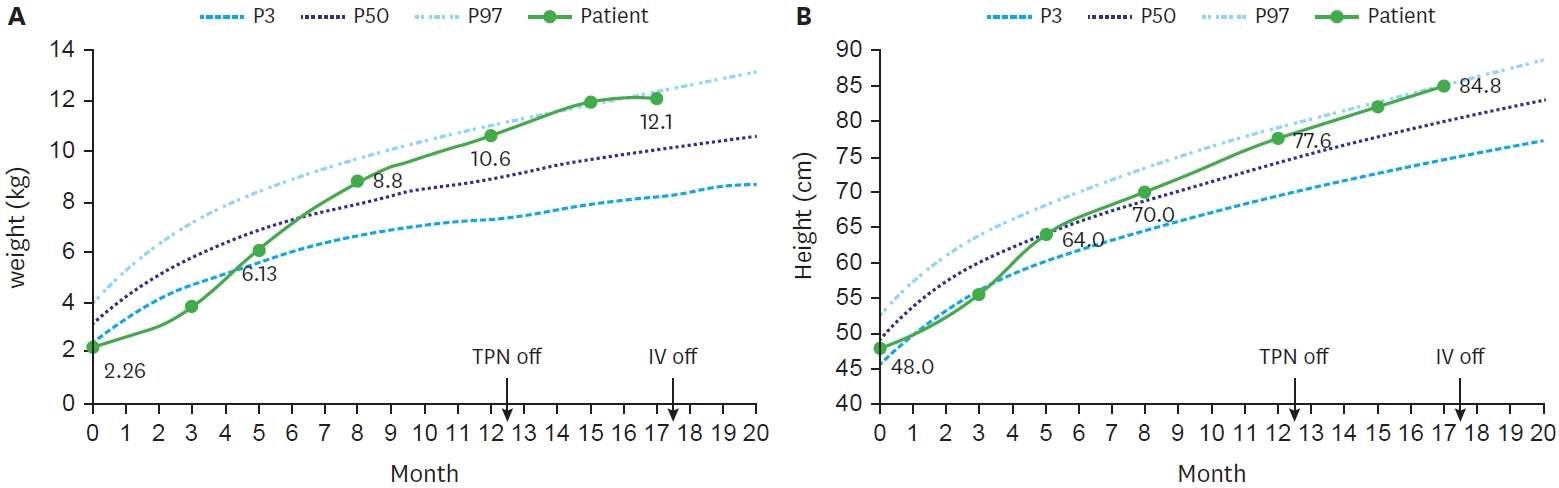

With continuous nutrition and growth monitoring, her condition improved at an acceptable rate. At birth, she was a premature infant with low birth weight below 3th percentile (2.26 kg), and height of 25 percentile (48 cm). However, by 5 months, her height had increased to 50th percentile (50 cm) and 75th percentile (70 cm) at 8 months, while her weight increased from 15th percentile (6.13 kg) to 75th percentile (8.8 kg). She kept maintained above 50

th percentile, and after discontinuing TPN at 12 months old, her height and weight peaked around 95th percentile (

Fig. 5).

Stool output was carefully monitored, with diarrhea defined as output exceeding 20 g/kg/d. A notable increase in stool occurred primarily around month 4, when she started increasing enteral feeding, and during the beginning of weaning food. Initially, we adjusted to reduce the amount of feeding and increase TPN fluids to maintain hydration and nutritional supply. After starting weaning food, we tried to modify the ingredients and used various lactobacilli supplements with intermittent antidiarrheal drugs (

Racecadotri, Hidrasec

® Abbott Korrea, Seoul, Korea). She is currently maintaining a stable stool condition with a normal pattern, averaging 2 times per day and around 6 g/kg (

Fig. 3). Through 20 months of follow-up, the patient demonstrated uncomplicated growth, so we gradually extended the outpatient visits and laboratory monitoring intervals from monthly to bimonthly. Last laboratory results taken at 20 months of age were all found to be normal, including liver function, albumin, heavy metals, and vitamins (

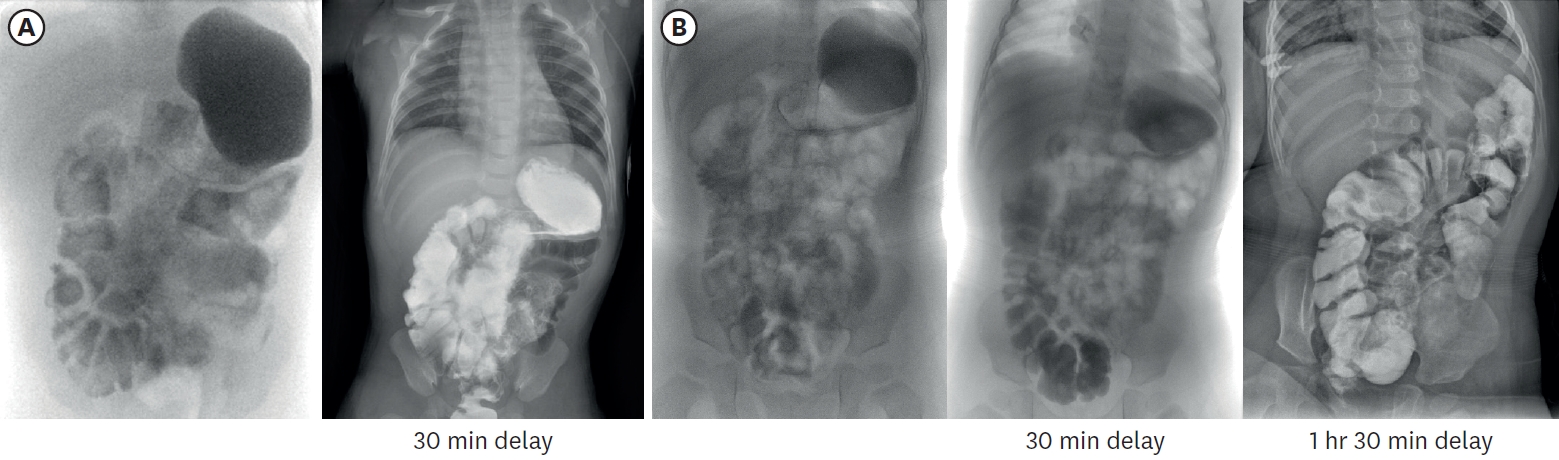

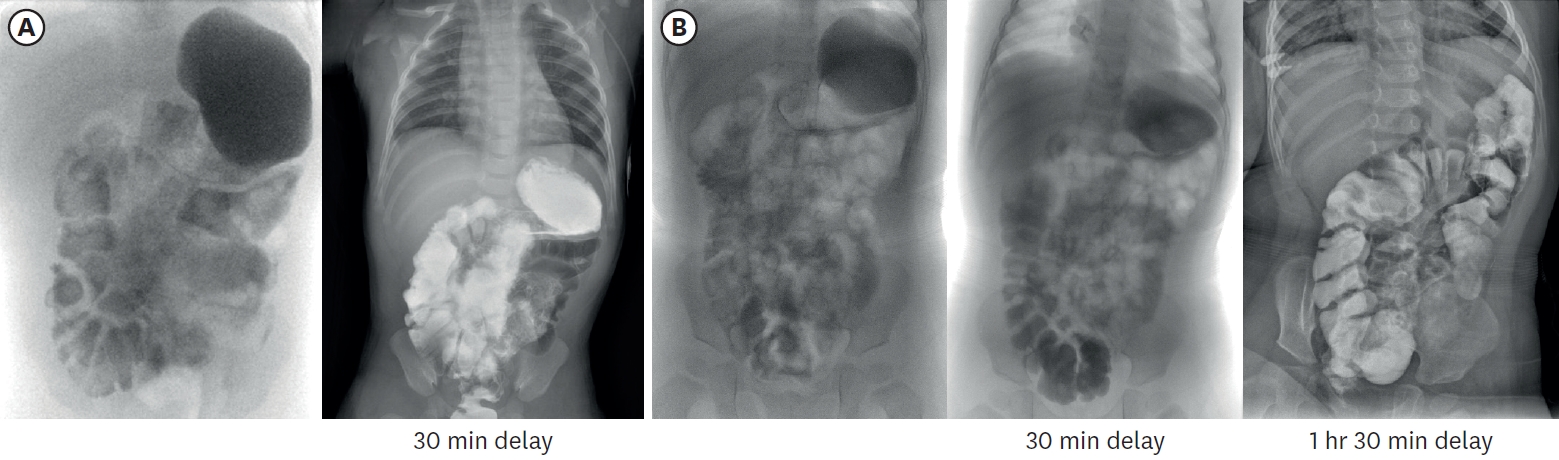

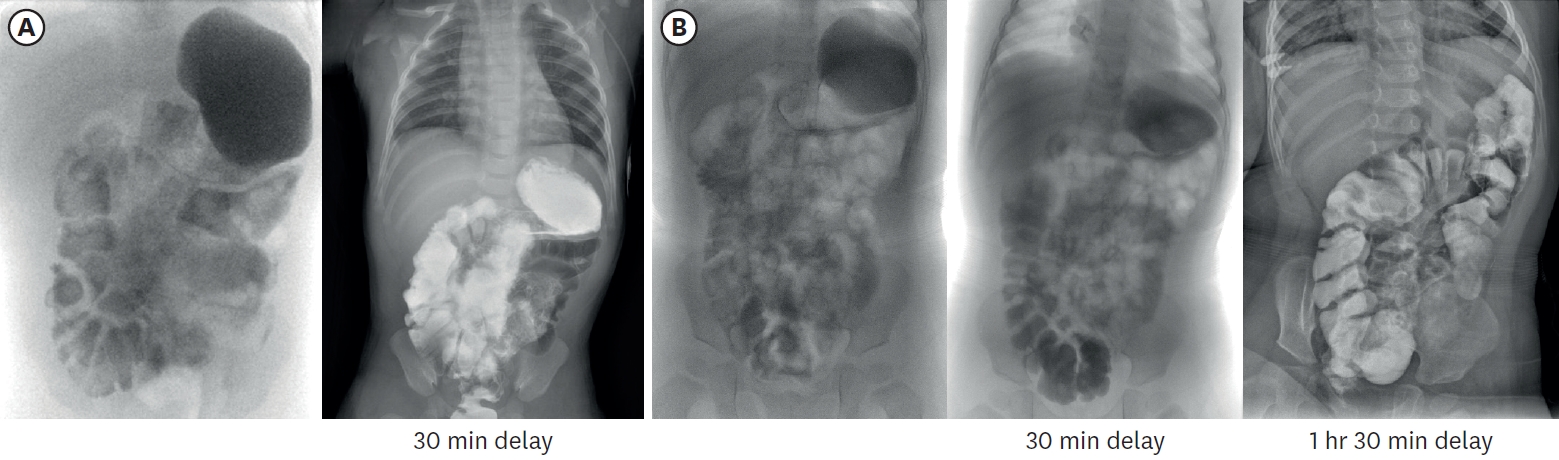

Table 1). To monitor the bowel’s adaptation process, small bowel series examination was undertaken at 3 months and 16 months of age respectively (

Fig. 6). It was noted that the IC valve transit time was increased more than twofold from 7 minutes to 14 minutes. This indicated an enhanced intestinal nutritional retention time, which resulted in improved nutrient absorption and overall intestinal function.

DISCUSSION

Patients with USBS experience high mortality and complication rates, because of the necessity to rely on long-term parenteral nutrition until their absorptive function recovers. This process of intestinal adaptation continues for about 2 years after surgical resection [

6,

7]. Stimulating this process is the key to of intestinal rehabilitation, as it leads to achieve enteral autonomy and discontinue parenteral nutrition, while also preventing and minimizing the long-term complications [

8]. This requires a multidisciplinary approach and ongoing research [

9].

Our case represents an exceptional case of an extremely SBS premature infant with a total 15 cm length of small bowel, being able to discontinue TPN at 12 months of age and achieve intestinal autonomy without any long-term complications. Meanwhile, according to the growth curve, the patient consistently reached above the 50th percentile after 8 months of age, and the nutritional lab values never significantly deviated from the normal range. This raises the question of whether parenteral nutrition could have been tapered a bit earlier than 12 months of age. However, considering the patient’s young age and intermittent episodes of diarrhea due to vaccinations or gastroenteritis, we decided that a more conservative and gradual reduction would be safer approach. In this manner, the physician and nutrition team carefully advanced the feeding rate by monitoring the patient’s stool output, vomiting, and abdominal distension. The key elements of our TPN protocol included: appropriate micronutrient supplementation with careful monitoring, implementation of cyclic infusion methods to facilitate enteral nutrition while preventing liver dysfunction, appropriate medical management of diarrhea, meticulous line care to prevent catheter related complications, and effective home based dietary management through accurate daily intake and output monitoring. In addition, about four decades ago when parenteral nutrition support was not as proactive as it is now, Wilmore announced that survival of SBS requires at least 15 cm of small intestine in the presence of the ileocecal valve or 40 cm without it [

10]. However, recent studies suggest that the anatomical region or the proportion of the remaining intestine, may be more significant than the actual remnant length [

11]. In our case, the presence of intact colon and the preservation of ileocecal valve along with 8cm of proximal terminal ileum [

11-

13] both served as a favorable prognostic factors. We believe that successful weaning from parenteral nutrition was achieved through the combination of these favorable anatomical conditions and our comprehensive TPN protocol management. A systematic and specialized treatment protocol and multidisciplinary approach should be essential for successful outcomes of USBS patients.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.J.H.; Data curation: J.Y., C.J.H.; Visualization: J.Y., C.J.H.; Writing - original draft: J.Y.; Writing - review & editing: C.J.H.

Fig. 1.Imaging performed after birth. (A) Infantogram showing multiple dilated loops of small bowel. (B) Following ultrasonography showing dilated proximal small bowel filled with fluid, without definite wall thickening or abnormal vascularity.

Fig. 2.Intraoperative images. From 7 cm below the Treitz ligament, entire small intestine was found to be atretic.

Fig. 3.Timeline graph showing clinical progression of stool, along with feeding advancement. Stool consistency patterns (normal: dotted, loose: diagonal lines, very loose: cross-hatched). Dark blue (total feeding amount), skyblue (weaning food), green (stool frequency), red (stool amount).

Fig. 4.

Diagram showing temporal progression of TPN protocol components (Infusion methods, Intake target, and TPN types) over a 17-month period of intestinal

rehabilitation. Key events marked at their respective time points.

TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Fig. 5.

Growth curve of the patient up to 20 months of age. (A) Patient’s body weight. (B) Patient’s height.

TPN, total parenteral nutrition; IV, intravenous.

Fig. 6.Small bowel series images taken at 3 months (A) and 16 months (B) of age respectively. In (A), contrast passage to rectum was observed after 30-minute delayed image, and total small bowel length was approximately 23.4 cm, including duodenum. In (B), contrast passage to ascending colon was observed after 30-minute delayed image, and total small bowel length was approximately 29.9 cm.

Table 1.Most recent laboratory results at 20 months of age

Table 1.

|

Blood test |

Unit |

Result |

Normal range |

|

Hemoglobin |

g/dL |

13.9 |

12.0–16.0 |

|

Hematocrit |

% |

44 |

34.0–49.0 |

|

Total protein |

g/dL |

6.6 |

6.6–8.7 |

|

Albumin |

g/dL |

4.6 |

3.5–5.2 |

|

Prealbumin |

mg/dL |

17 |

20–40 |

|

Total bilirubin |

mg/dL |

0.5 |

0–1.2 |

|

GOT |

U/L |

35 |

0–32 |

|

GPT |

U/L |

28 |

0–33 |

|

Transferrin |

mg/dL |

284 |

200–360 |

|

Iron |

mcg/dl |

65 |

33–193 |

|

Zinc |

ug/dL |

106 |

|

|

Copper |

ug/dL |

123 |

64–134 |

|

Mangane |

ug/L |

14.7 |

<8.0 |

|

Chromium |

μg/dL |

0.2 |

≤1.00 |

|

Selenium |

μg/dL |

8.1 |

5.8–23.4 |

|

25(OH) vitamin D total |

ng/mL |

46.3 |

>20 |

|

Folic acid |

ng/mL |

32.3 |

>5.38 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Khan FA, Squires RH, Litman HJ, Balint J, Carter BA, Fisher JG, et al. Predictors of enteral autonomy in children with intestinal failure: a multicenter cohort study. J Pediatr 2015;167:29-34.e1.

- 2. Mangalat N, Teckman J. Pediatric intestinal failure review. Children (Basel) 2018;5:100.

- 3. Batra A, Keys SC, Johnson MJ, Wheeler RA, Beattie RM. Epidemiology, management and outcome of ultrashort bowel syndrome in infancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F551-6.

- 4. Belza C, Wales PW. Multidisciplinary management in pediatric ultrashort bowel syndrome. J Multidiscip Healthc 2020;13:9-17.

- 5. Joosten K, Embleton N, Yan W, Senterre T, Braegger C, Bronsky J, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: Energy. Clin Nutr 2018;37:2309-14.

- 6. Lakkasani S, Seth D, Khokhar I, Touza M, Dacosta TJ. Concise review on short bowel syndrome: etiology, pathophysiology, and management. World J Clin Cases 2022;10:11273-82.

- 7. Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Rausa E, Invernizzi P, Braga M, Vecchi M. Understanding short bowel syndrome: Current status and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis 2020;52:253-61.

- 8. Duggan CP, Jaksic T. Pediatric intestinal failure. N Engl J Med 2017;377:666-75.

- 9. Stanger JD, Oliveira C, Blackmore C, Avitzur Y, Wales PW. The impact of multi-disciplinary intestinal rehabilitation programs on the outcome of pediatric patients with intestinal failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:983-92.

- 10. Wilmore DW. Factors correlating with a successful outcome following extensive intestinal resection in newborn infants. J Pediatr 1972;80:88-95.

- 11. Spencer AU, Neaga A, West B, Safran J, Brown P, Btaiche I, et al. Pediatric short bowel syndrome: redefining predictors of success. Ann Surg 2005;242:403-9.

- 12. Hasegawa T, Sumimura J, Nose K, Sasaki T, Miki Y, Dezawa T. Congenital multiple intestinal atresia successfully treated with multiple anastomoses in a premature neonate: report of a case. Surg Today 1996;26:849-51.

- 13. Amin SC, Pappas C, Iyengar H, Maheshwari A. Short bowel syndrome in the NICU. Clin Perinatol 2013;40:53-68.