ABSTRACT

Proliferative myositis (PM) is a rare benign soft tissue neoplasm with a distinctive pseudosarcomatous proliferative reaction of muscles in tumors. Its rapid growth and bizarre microscopic appearance often require a differential diagnosis from a sarcomatous lesion. It has been reported occasionally, mostly as case reports in adult patients. Herein, we present a neonatal case of PM. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the neonatal period.

-

Keywords: Soft tissue neoplasm; Proliferative myositis; Neonate

INTRODUCTION

Proliferative myositis (PM) is a rare and benign soft tissue tumor first described by Kern [

1] in 1960 as a pseudosarcomatous reaction to injury. Typically, PM manifests as a solitary mass and is commonly found in the shoulder, proximal limbs, trunk, head, or neck [

2,

3]. Due to its rapid growth, PM is often mistaken for aggressive malignant tumors, such as sarcoma [

4,

5]. The clinical and imaging features of PM are frequently ambiguous, which can result in unnecessary extensive resections under suspicion of malignancy [

2]. This diagnostic challenge is particularly significant in children, among whom PM is rare, as the lesion predominantly occurs in adults [

4,

6,

7]. To expand the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors in pediatric populations, we report a case of PM identified in a neonate, underscoring the importance of considering PM in the diagnostic workup for similar presentations in children.

CASE REPORT

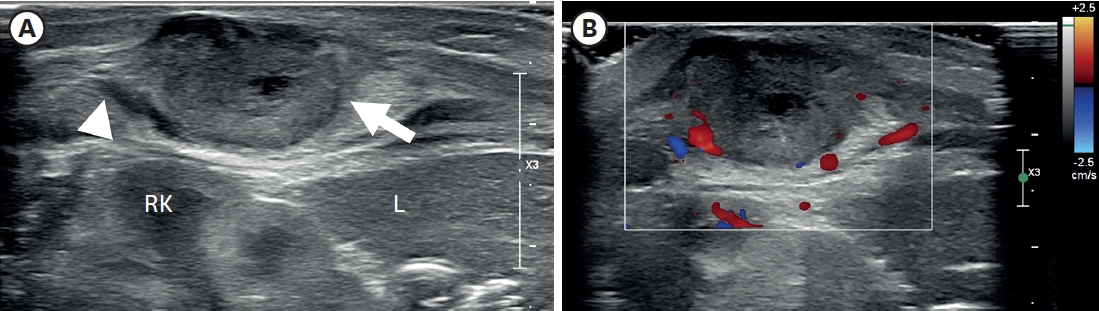

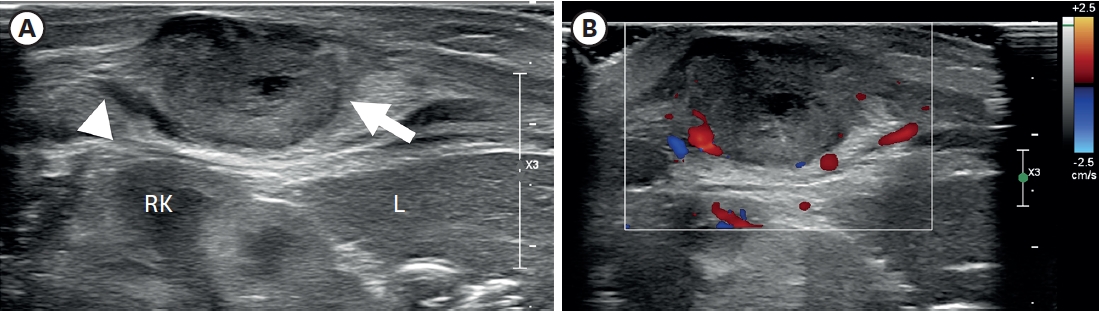

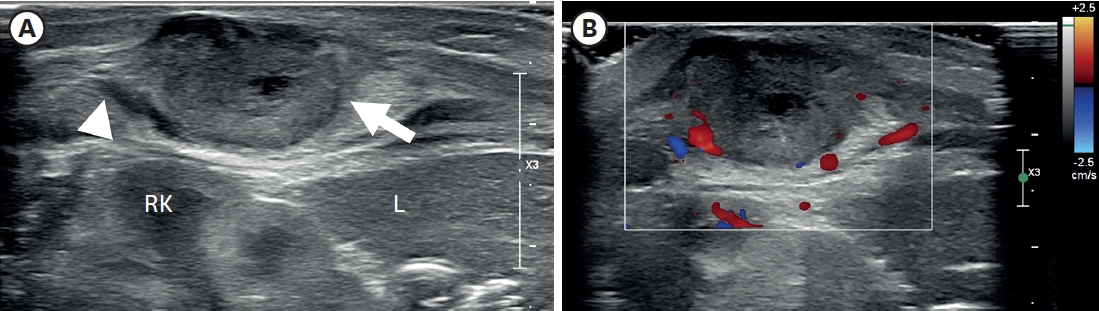

A 3.3 kg female baby was born at 39 weeks gestation with a mass on the right chest wall, and she was admitted to the hospital. Except for the mass, the patient was healthy and had no comorbid diseases such as congenital anomalies. The mass was approximately 3 cm long, hard, fixed, and well defined, with no symptoms such as pain or skin changes. The ultrasound (US) examination (

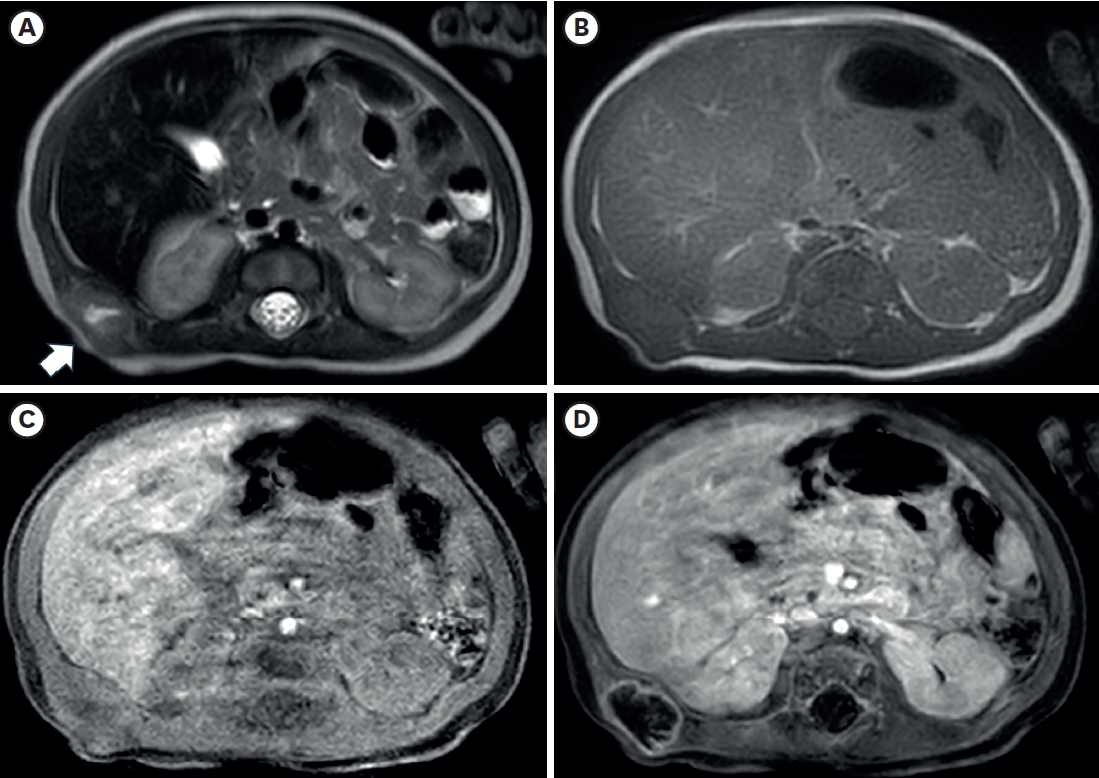

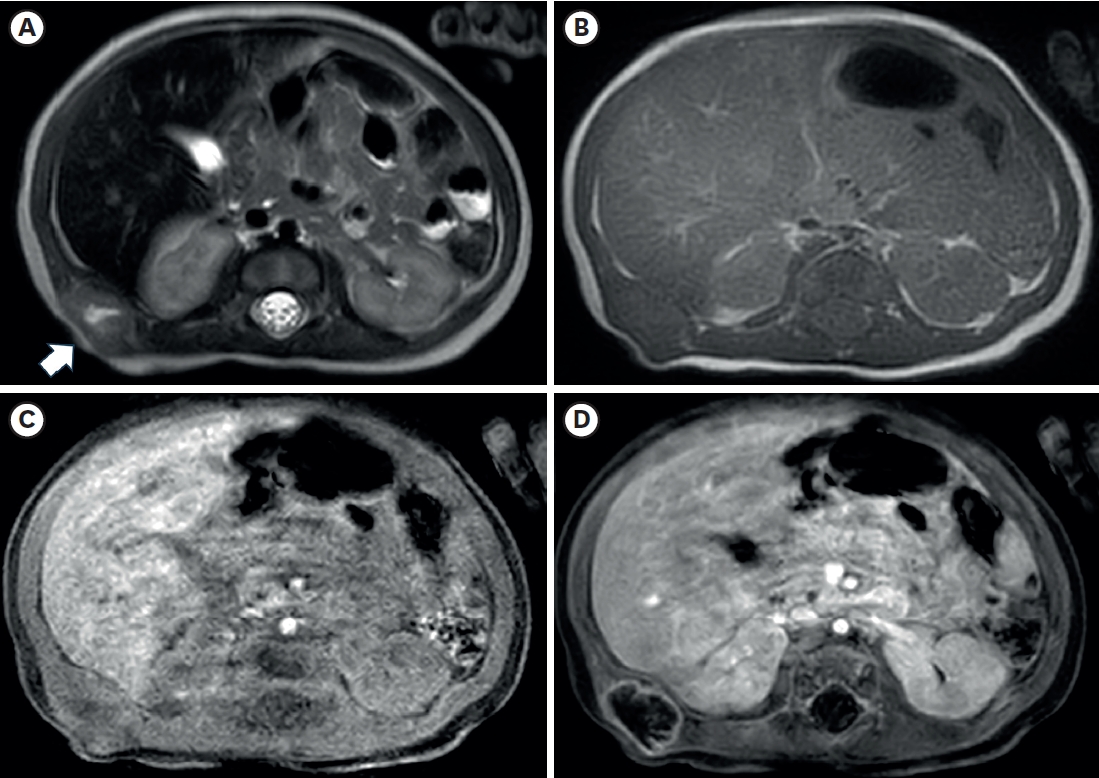

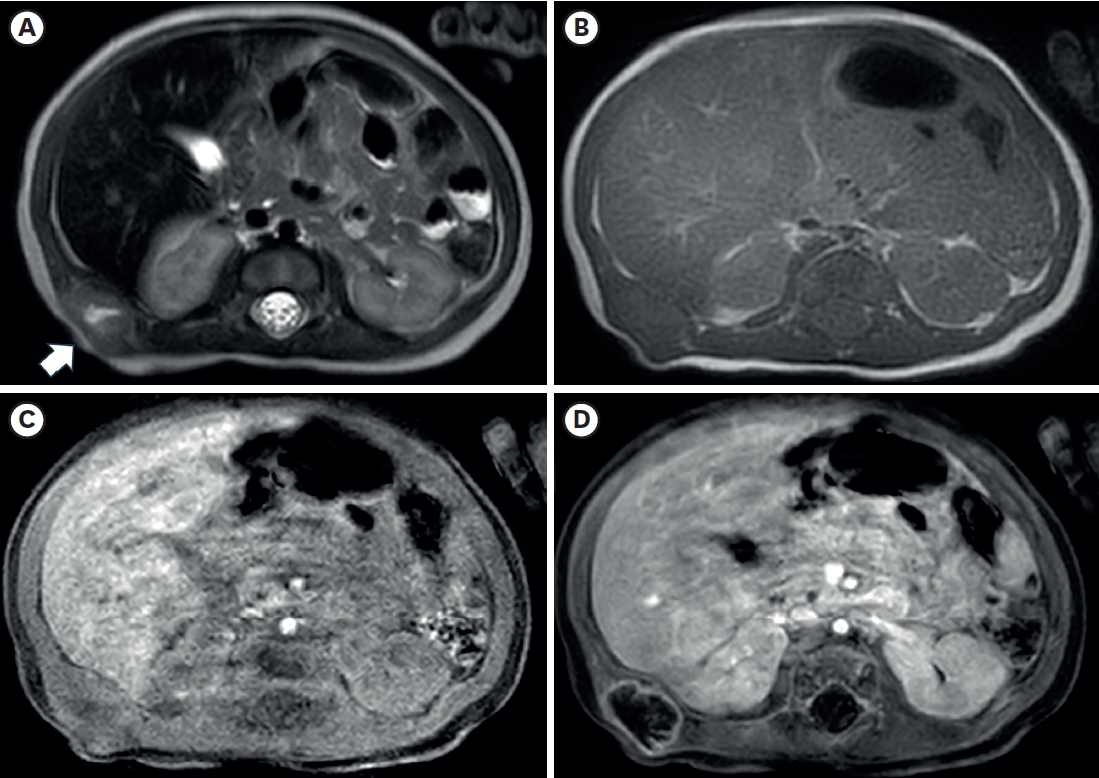

Fig. 1) showed a lobulated soft tissue lesion in the muscular layer, with an internal necrotic hypoechoic portion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI,

Fig. 2) also showed a lobulated mass with central necrosis, a well-defined margin, and peripheral rim enhancement in the muscular layer. The patient underwent surgical excision on the 20th day of birth for accurate diagnosis and treatment. In the operative findings, the mass was located in the latissimus dorsi muscle and butted to the right 12th rib, but dissection was performed without difficulties or injury to adjacent structures.

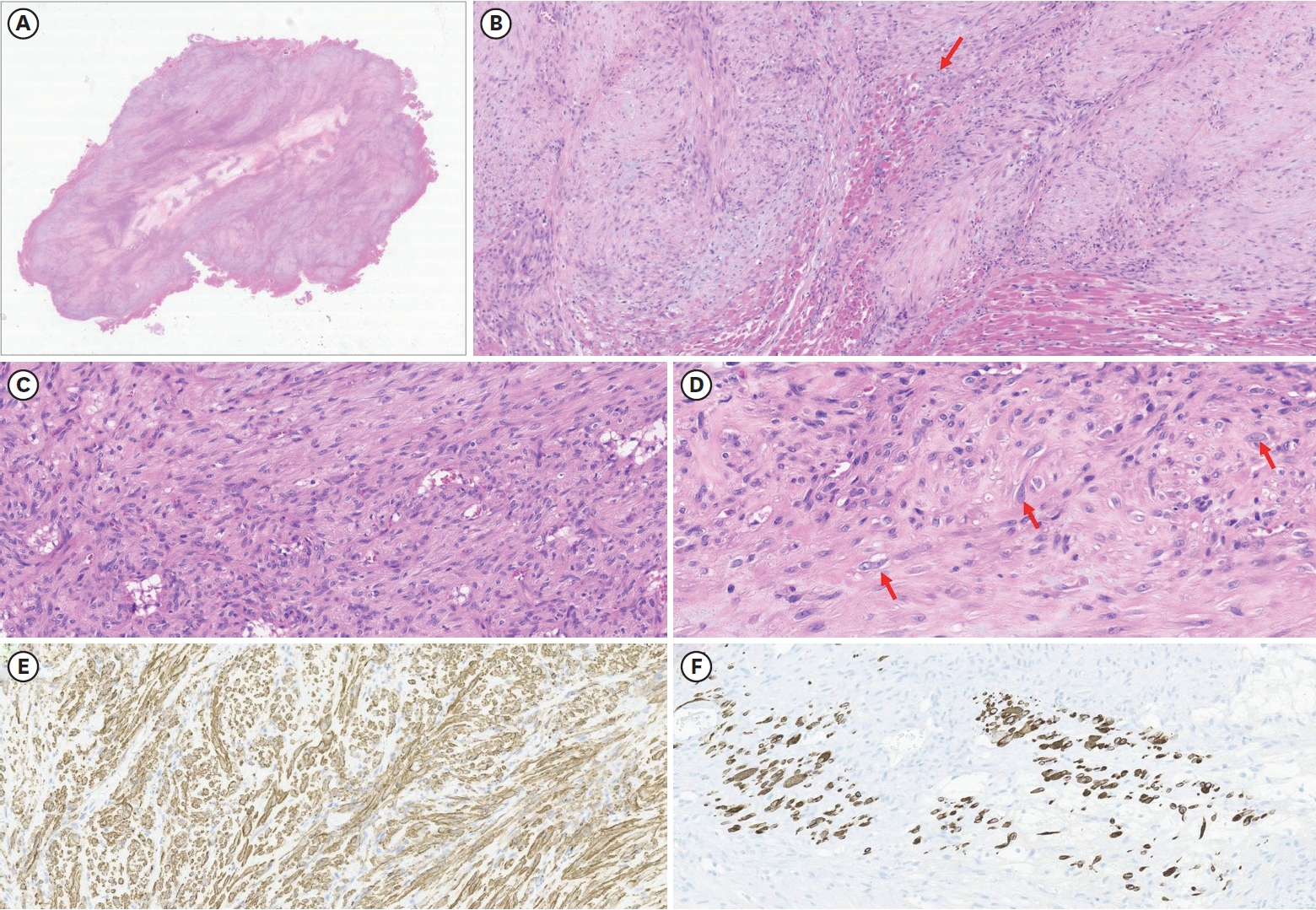

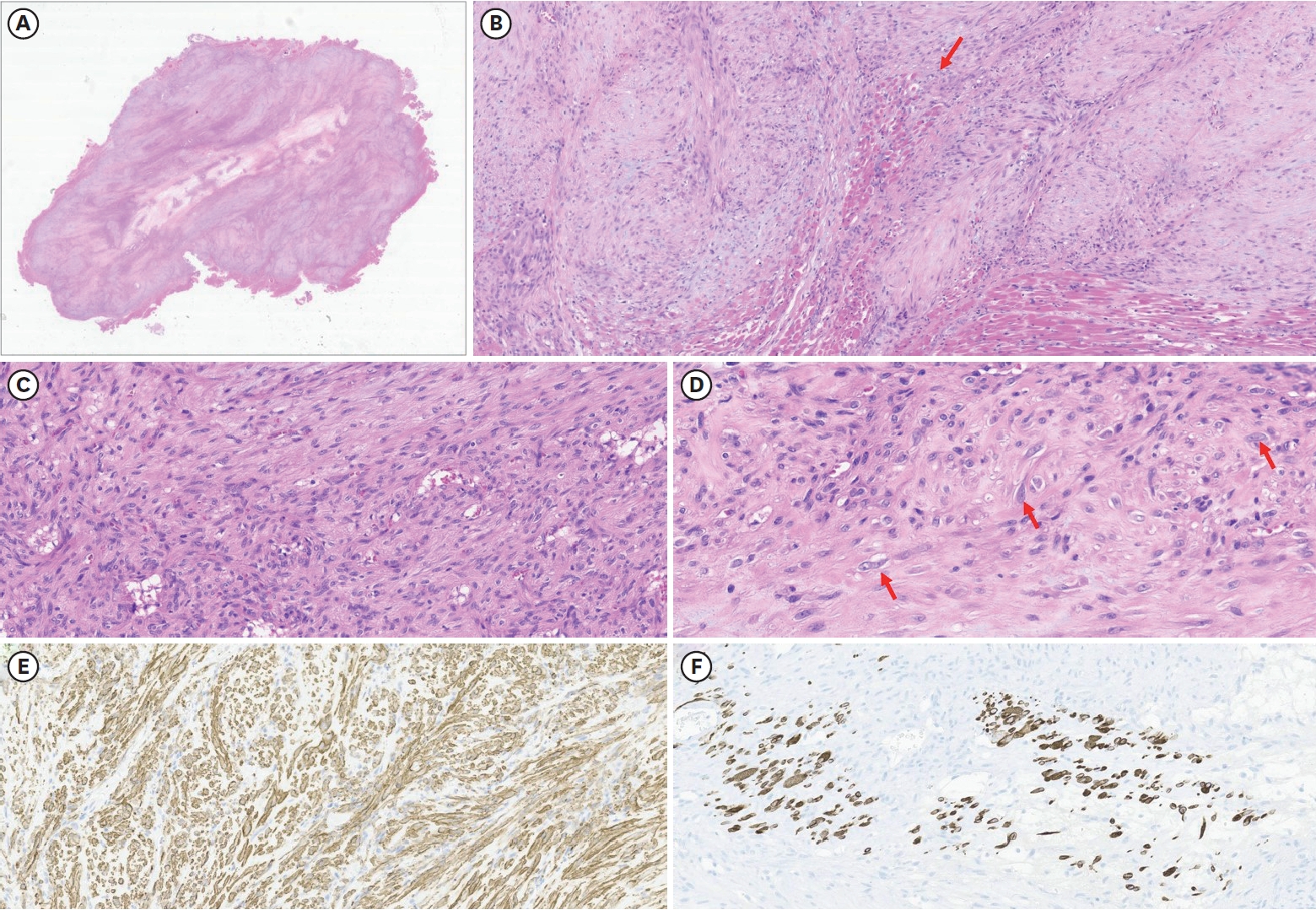

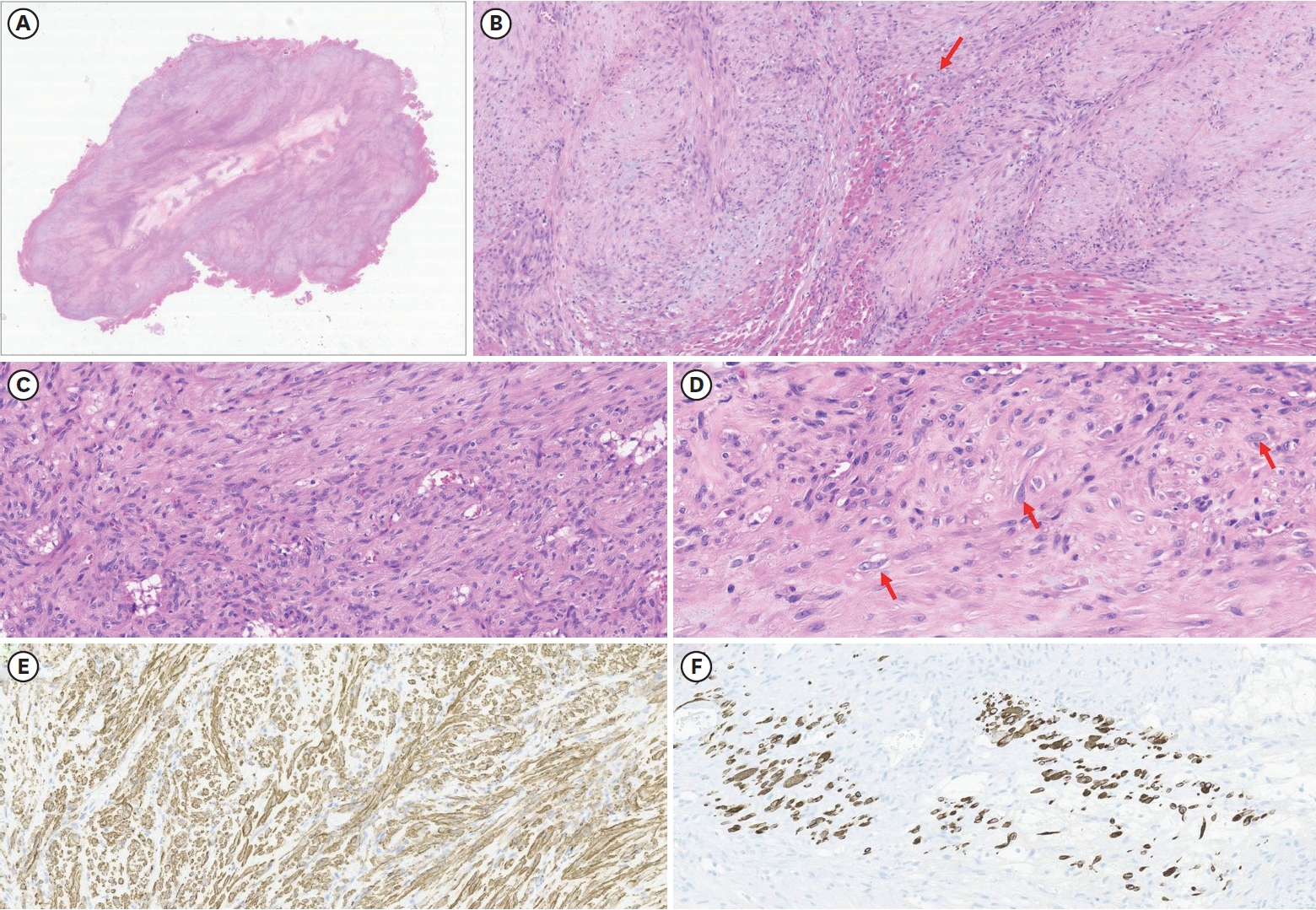

Histopathological findings (

Fig. 3) showed a few ganglion-like cells and fibroblastic proliferation, which were compatible with PM characteristics. There was no hemorrhage or necrosis, but central degeneration was noted.

The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6 without any complications and with no recurrence of the lesion for the 3-year follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

PM is a rare, benign tumor of soft tissue. Since Kern first described it in 1960 [

1], it has been occasionally reported in the literature, most of which are case reports. It has a distinctive pseudosarcomatous proliferative reaction of muscles in tumors, and its rapid growth and bizarre microscopic appearance often require a differential diagnosis from a sarcomatous lesion [

4-

6]. Its clinical characteristics are nonspecific [

2,

3]. The mass is usually solitary and often presents as a firm, fixed, painless nodule. The tumors are usually less than 5 cm in size, which is preferred in the upper extremities, but any muscle can be involved. Almost all PMs are found in adults and are rare in childhood. To our knowledge, this is the first report in the neonatal period.

The radiologic findings of PM are also not specific [

8,

9]. Some cases show the characteristic ultrasonographic findings of the checkerboard, dry-cracked mud, or steel cable-like pattern, but they are not observed in all PM cases. MRI is one of the preferred imaging modalities in children, but there is limited information about PM because of its rarity. Previous studies have reported that PM showed hypointense to isointense to muscle on non-contrast T1 weight sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences [

2,

10,

11]. In this case, the preoperative US showed internal hypoechoic lesions, and the MRI also showed an internal hyperintense portion on the T2-weighted image, which suggested internal necrosis. These lesions were proven to be central degeneration without hemorrhage or necrosis. These findings have not been reported previously, and they could be one of the possible radiologic findings of PM.

Typical histopathologic findings of PM include the proliferation of dense spindle-shaped fibroblasts and ganglion-like giant cells, which resemble rhabdomyoblasts. Their presence can lead to a misdiagnosis of sarcoma [

12,

13]. This case also had these two characteristics, supporting the diagnosis of PM.

The treatment of PM is controversial. Few studies have reported that it tends to regress spontaneously and have advocated waiting and seeing [

14,

15]. However, surgical excision is a good option for treatment because it is difficult to differentiate from sarcomatous lesions [

4,

16]. Excision was not complicated in this case, and other reports did not report the difficulties of surgical treatment either. However, it is essential to consider the possibility of PM when performing surgery, because misdiagnosing the lesion as a malignant tumor could lead to unnecessarily extensive resection and subsequent cosmetic or neurological complications.

In summary, this is the first report of a neonatal PM case. Although this disease is very rarely found in pediatric patients, when encountering a firm and rapidly growing mass, PM should be considered a possible disease.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.H.J., O.J.T.; Data curation: Y.H.J., K.J.Y., L.M.J., O.J.T.; Methodology: Y.H.J.; Supervision: O.J.T.; Validation: Y.H.J., O.J.T.; Writing - original draft: Y.H.J.; Writing - review & editing: O.J.T.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonography of the right flank palpable lesion. (A) A lobulated soft tissue lesion (arrow) and is connected with (arrowhead) the muscular layer of the body wall, just outside of the RK and L, with an internal necrotic hypoechoic portion. (B) Doppler study shows increased vascularity in the mass lesion’s peripheral portion and surrounding areas.

RK, right kidney; L, liver.

Fig. 2.Axial images of chest magnetic resonance imaging. (A) A lobulated soft tissue lesion (arrow) in the muscular layer of the body wall, just outside the right kidney and liver, with the internal cystic or necrotic portion on the T2-weighted image. The solid portion of the lesion shows (A) slightly high signal intensity compared with muscle on the T2-weighted image and (B) iso signal intensity on the T1-weighted image. T1-weighted axial images with fat suppression before (C) and after (D) contrast enhancement show only the lesion’s peripheral wall enhancement without filling the contrast material.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological findings. (A) Light microscopy reveals poorly circumscribed mass-forming lesions surrounded by skeletal muscle. No hemorrhage or necrosis was identified. However, central degeneration was noted (HE, 4×). (B) The lesion has an ill-defined border, and some entrapped skeletal muscle fibers are noted (arrow). The lesion is mainly composed of spindled cells. The stroma of the lesions is collagenous and myxoid (HE, 100×). (C) Most of the spindled cells show no atypia or mitosis. Minimal inflammatory cells are noted (HE, 200×). (D) High-power view of the lesion reveals a few ganglion-like cells, a histological characteristic of proliferative myositis (arrow) (HE, 400×). (E) Spindled cells were positive for smooth muscle actin, supporting fibroblastic proliferation, the other histologic finding of the tumor. (F) Desmin staining confirmed entrapped atrophic skeletal muscle fibers, suggesting tumor extension between individual muscle fibers (immunohistochemistry, 200×).

HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kern WH. Proliferative myositis; a pseudosarcomatous reaction to injury: a report of seven cases. Arch Pathol 1960;69:209-16.

- 2. Trerattanavong P, Suriyonplengsaeng C, Waisayarat J. Proliferative myositis: a comprehensive review of 33 case reports. Rama Med J 2019;42:60-70.

- 3. Enzinger FM, Dulcey F. Proliferative myositis. Report of thirty-three cases. Cancer 1967;20:2213-23.

- 4. Acharya AS, Kulkarni RV, Patrike SB, Nair SG. Proliferative myositis: a rare pseudosarcoma in children. J Clin Case Rep 2015;5:1000487.

- 5. Rosenberg AE. Pseudosarcomas of soft tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:579-86.

- 6. Talbert RJ, Laor T, Yin H. Proliferative myositis: expanding the differential diagnosis of a soft tissue mass in infancy. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:1623-7.

- 7. Meis JM, Enzinger FM. Proliferative fasciitis and myositis of childhood. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:364-72.

- 8. Yiğit H, Turgut AT, Koşar P, Astarci HM, Koşar U. Proliferative myositis presenting with a checkerboard-like pattern on CT. Diagn Interv Radiol 2009;15:139-42.

- 9. Pagonidis K, Raissaki M, Gourtsoyiannis N. Proliferative myositis: value of imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005;29:108-11.

- 10. Celikyay F, Yuksekkaya RZ, Deveci S. The web-like pattern on MRI of proliferative myositis. Joint Bone Spine 2022;89:105389.

- 11. Demir MK, Beser M, Akinci O. Case 118: proliferative myositis. Radiology 2007;244:613-6.

- 12. Pasquel P, Salazar M, Marvan E. Proliferative myositis in an infant: report of a case with electron microscopic observations. Pediatr Pathol 1988;8:545-51.

- 13. Orlowski W, Freedman PD, Lumerman H. Proliferative myositis of the masseter muscle. A case report and a review of the literature. Cancer 1983;52:904-8.

- 14. Kim BH, Jang W, Kim SW, Jeong WJ. A case of proliferative myositis arising from the sternocleidomastoid muscles diagnosis and treatment. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2020;63:537-40.

- 15. Brooks JK, Scheper MA, Kramer RE, Papadimitriou JC, Sauk JJ, Nikitakis NG. Intraoral proliferative myositis: case report and literature review. Head Neck 2007;29:416-20.

- 16. Recarey FJR, Luis PC, Guerrero RBM. Proliferative myositis of the gastrocnemius muscle: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2008;18:479-82.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by