ABSTRACT

Pediatric intestinal perforation is a surgical emergency that must be promptly addressed regardless of the specific cause. Here we report a case of colon perforation caused by indeterminate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in an autistic 13-year-old boy. Ulcerative colitis (UC) and lymphoma were first suspected but subsequently ruled out. The patient was previously hospitalized locally for 8 days due to diarrhea. He was diagnosed with UC and colon perforation in the emergency room. He then underwent subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy. Pathological examination of the colon showed multiple perforations with absence of chronic crypt change (a characteristic of UC), presence of undermining ulcers, and atypical lymphocyte infiltrations. Lymphoma was ruled out from immunohistochemistry and blood tests. Indeterminate colitis was finally suggested as the cause of perforation. Genetic analysis confirmed KBG syndrome, but no abnormalities otherwise known to be relevant to colitis. This case demonstrates that spontaneous colon perforation might occur in KBG syndrome patients suffering from severe enteritis without IBD, malignancy, or other conditions known to cause perforation, supporting the necessity of close monitoring when such patients present with severe symptoms including fever and abdominal distension without showing improvement.

-

Keywords: Children; Intestinal perforation; Colitis

INTRODUCTION

Although intestinal perforation in children is rare, it is a pediatric surgical emergency with varied etiology that must be promptly addressed regardless of the cause [

1]. Trauma and necrotizing enterocolitis are better-known causes of pediatric intestinal perforation. Other possible causes include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and malignancy such as lymphoma and colorectal cancer [

2]. Here we report a case of pediatric colon perforation in which the patient preoperatively diagnosed with perforation caused by ulcerative colitis (UC) underwent subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy. After ruling out UC and lymphoma, the final diagnosis was spontaneous colon perforation caused by severe enteritis, with suspected acute manifestation of indeterminate colitis (IC). Notably, later genetic analysis diagnosed the patient with KBG syndrome, a rare genetic disorder known to cause neurological and skeletal manifestations but not associated with colitis.

CASE REPORT

A 13-year-old boy was referred to the pediatric emergency room due to suspected bowel perforation and panperitonitis. He was hospitalized for diarrhea at a local clinic 8 days prior and referred to another ER the day before. Computerized tomography (CT) scans had demonstrated diffuse dilatation of colon with pneumatosis intestinalis suggestive of toxic megacolon (

Fig. 1). His underlying conditions included autism and developmental delay (mental retardation). Although the patient displayed facial dysmorphism and inability to flex both 5th finger proximal interphalangeal joints, no genetic study or chromosomal microarray test had been performed before. At admission, a review of systems revealed histories of fever, cough, nausea, hematochezia, and abdominal pain.

Physical examination of the patient marked abdominal distension and tympanic bowel percussion sound with diffuse abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness. Abdominal X-ray taken on the operative day suggested bowel perforation. CT scans demonstrated massive amounts of free air, leading to a strong suspicion of pneumoperitoneum and bowel perforation. Chest X-ray imaging found no active lung lesions. Taking the patient’s underlying conditions into account along with physical and radiological findings, UC with colon perforation was diagnosed. The patient then underwent a subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy.

During operation, surgical exploration found colon wall defects at the hepatic flexure, the transverse colon, the splenic flexure, and around the middle of the descending colon. As the rectum appeared to have been spared, subtotal colectomy could be performed successfully without warranting further dissection. On the third postoperative day, the patient’s hemoglobin level fell to 7.7 g/dL, which required transfusion. There was massive hematochezia through the anus on the sixth operative day without active bleeding found on CT scans, probably due to bleeding in the rectal stump.

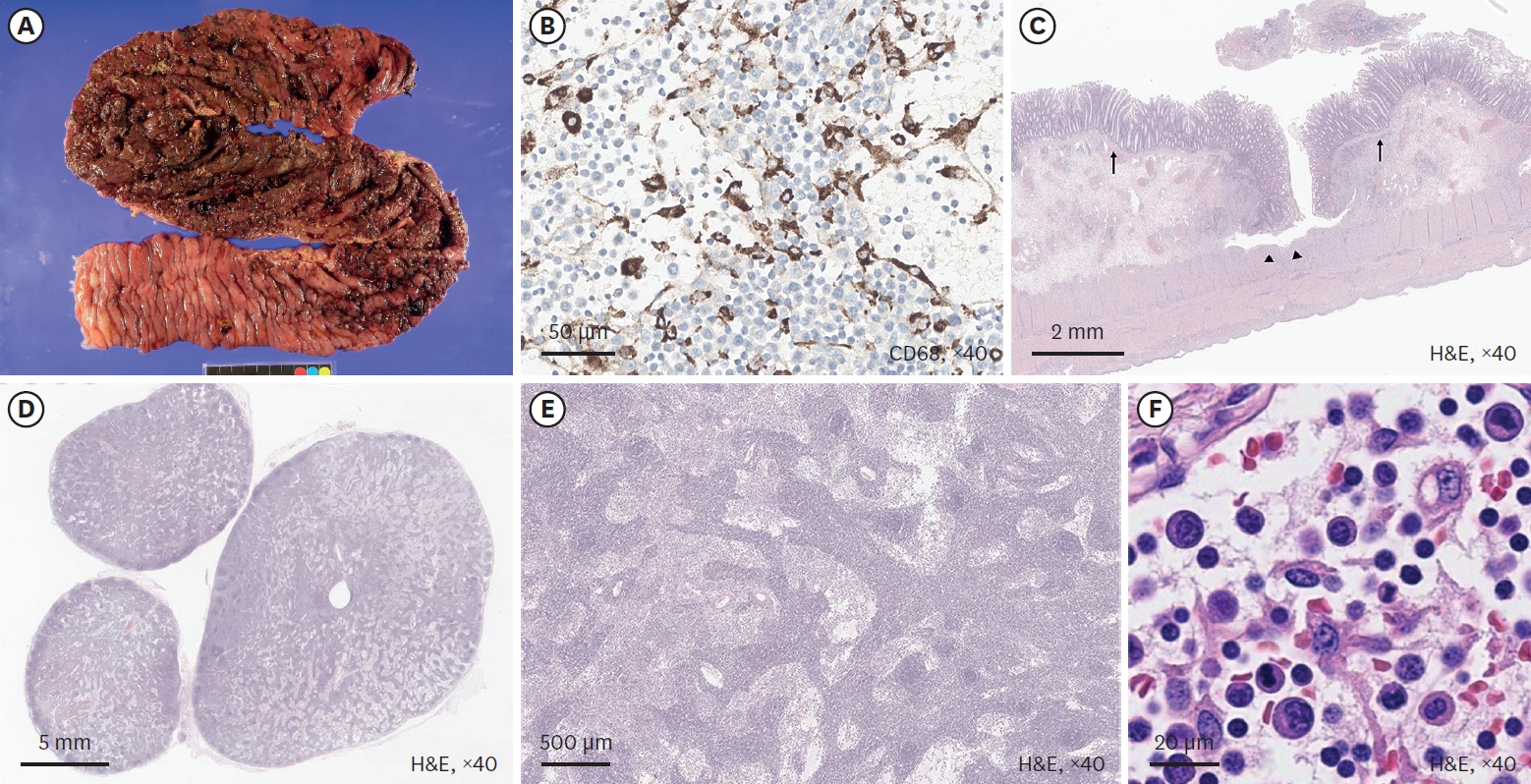

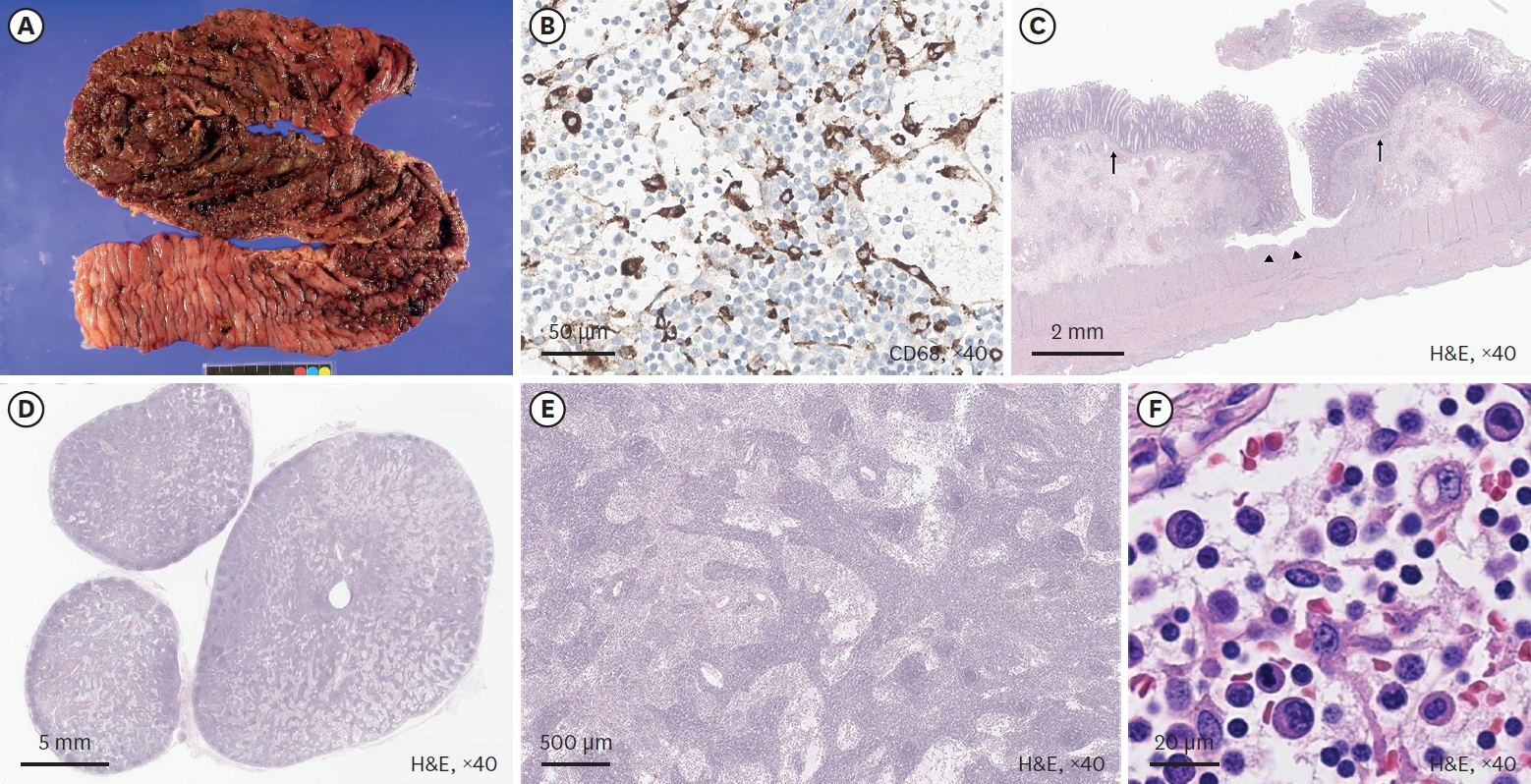

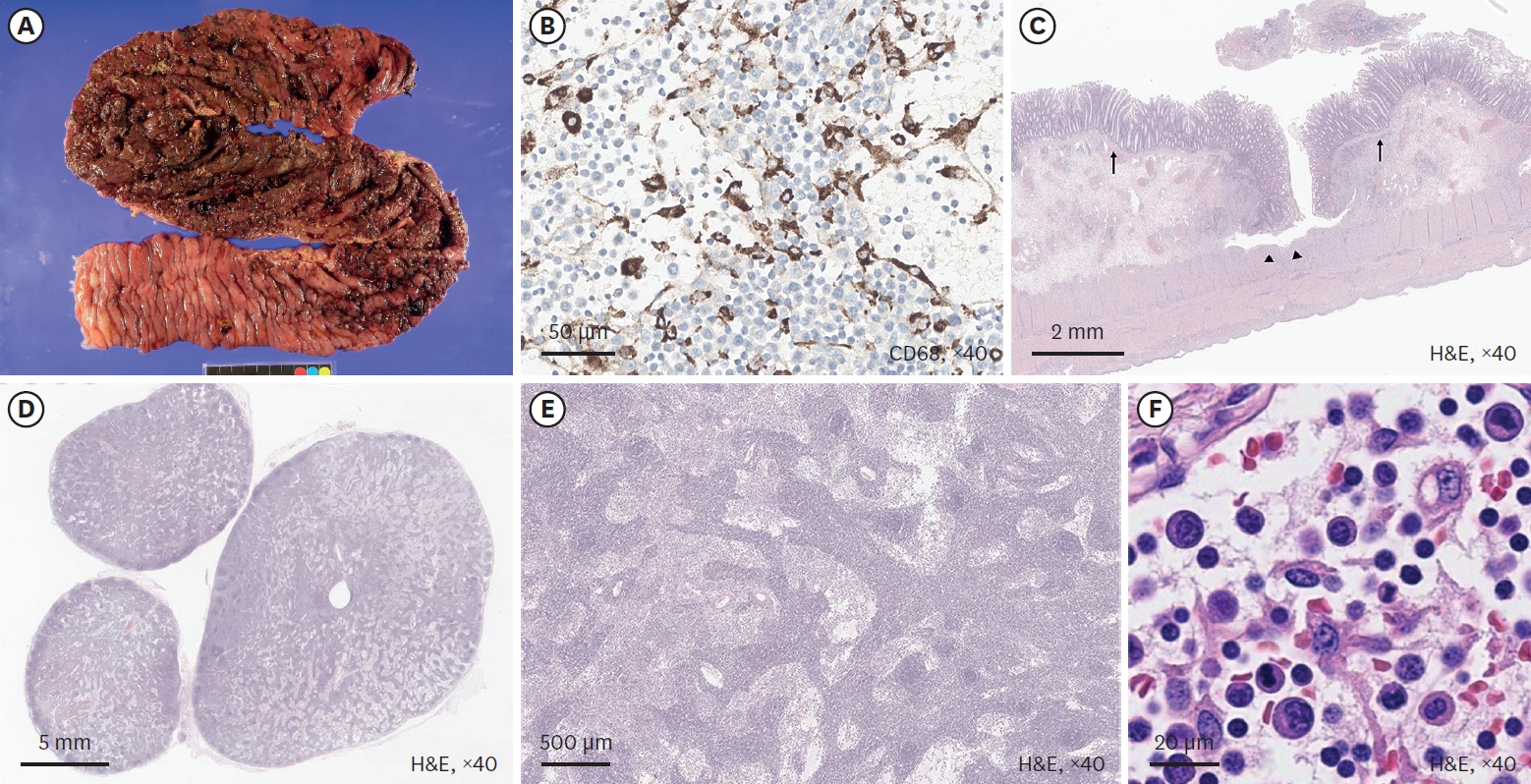

Pathological examination of the colon (

Fig. 2) showed diffuse segmental mucosal ischemia with multiple undermining ulceration (

Fig. 2A) and perforation along with submucosal and subserosal congestion. However, the distal resection margin was confirmed as viable, indicating rectal sparing. Defects in the intestinal wall were observed in areas presumed to be transverse and descending colons. Contrary to the preoperative diagnosis, no clear finding indicative of UC was noted. Although there were ulcers throughout the resected colon, their extension into the muscularis propria was thought to be incompatible with UC. Lack of cryptitis (

Fig. 2B) and extreme plasmacyte-dominant lymphocyte infiltration (

Fig. 2C and

D) also contradicted UC. Extremely enlarged lymph nodes (

Fig. 2E) and atypical lymphocyte aggregation (

Fig. 2F) were notable. These were later determined to be macrophages by CD68 staining. T-cell receptor (TCR) rearrangement analysis showed monoclonality within a lymph node but not in the bowel infiltration. These additional immunohistochemistry and TCR clonality results led to the conclusion of a low possibility of malignant lymphoma, although there were scattered atypical cell infiltrations in both bowel and lymph nodes. A blood test performed on the 12th postoperative day found no evidence of cytopenia or hyperuricemia indicative of tumor lysis syndrome. IC was finally suggested as the cause of perforation. The patient was discharged. He showed no other signs of malignancy or IBD up to 11 months after surgery.

However, some clinical and pathological factors did not entirely match typical presentation of IC, including the acute nature of fulminant colitis and the monoclonality found in lymph node T cells. The lymphoblastic appearance of aggregated lymphocytes initially led to a suspicion of lymphoma which was later discarded based on the patient’s clinical course. Trio-exome sequencing found heterozygous ANKRD11 deletion of maternal inheritance (c:1903_1907del, p.Lys635GInfsTer26), leading to a diagnosis of KBG syndrome, a rare genetic disorder not previously reported to have an association with colitis or other lower intestinal disorders.

1. Institutional Review Board (IRB) statement

IRB review was waived due to the retrospective nature of this report.

DISCUSSION

Intestinal perforation in children might be caused by a variety of conditions such as trauma, ischemia, diverticulitis, IBD, and cancer [

2]. The surgical approach is usually selected between primary repair and colostomy depending on the circumstance [

1]. Other known causes for pediatric intestinal perforations include Hirschsprung’s disease, IBD (including UC), connective tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) type IV [

3], lymphoma, and infective colitis. Despite the wide range, the etiology for perforation remains unknown for a significant portion of children [

1]. Although spontaneous perforation of normal colon without preceding conditions is rare in children, it must be suspected in children presenting with sustained fever and sudden abdominal distention [

4].

For children with non-traumatic colon perforation beyond the neonatal period, IBD and cancer perforation might be considered as possible causes. In the present case, UC had been diagnosed in the beginning based on the patient’s clinical presentation and radiological findings. Although UC is a disease that commonly begins in adulthood, pediatric UC shares many features with adult-onset of the disease; early diarrhea with rectal bleeding is a common presentation, and is accompanied by severe colitis in up to 10% of patients [

5]. Although the surgery rate for UC is declining with increasing use of advanced medical therapies including biological agents [

6], intestinal perforation, a relatively rare complication, remains a major cause for surgery along with uncontrolled bleeding and medical intractability [

7]. In the present case, the rectum had appeared relatively free of inflammation during surgery and in pathologic examination. Although rectal sparing is relatively common in children with newly-onset UC and known to be relevant to more acute exacerbations [

8,

9], UC was eventually excluded in this case due to other pathological findings (the extension of ulcers into the muscularis propria, their undermining appearance, and the absence of chronic crypt change, along with the atypical lymphocyte infiltration).

Malignancy is another important cause of intestinal perforation, although primary malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract is rare in children. Lymphoma constitutes a large part of pediatric gastrointestinal malignancy, as it might cause perforation either as an initial presentation of the disease or during treatment. In the present case, pathological examination found diffuse infiltration of atypical lymphocytes of unclear lineage in the mucosa, submucosa, and vascular lumen, as well as ten pericolic lymph nodes. However, the infiltration was heterogeneous. It did not match any known lymphoma categories. TCR gene rearrangement test found monoclonal T cells in a lymph node section. Since there were no other signs of T cell lymphoma, this was eventually considered to be an acute stage of lymphocyte proliferation (albeit unusual in its extreme reaction). From this and results from the blood test, lymphoma was excluded as the cause of perforation.

Less frequent causes for nontraumatic intestinal perforation in children include IBD other than UC, connective tissue diseases, and infective colitis. Mucosa and vessel walls did not show changes associated with EDS type IV. Infective colitis and CD were also ruled out, although so were diagnoses other than IBD. IC was finally suggested as the alternative plausible explanation for the perforation. The presence of broad-based, undermining ulcers, as well as the rectal sparing in gross examination, was consistent with typical pathological presentations of IC.

IC was historically a histopathological interim term for IBD where a definite diagnosis of either UC or CD could not be established based on available information, introduced in 1978 by Price and reported to account for approximately 10% to 15% of IBD specimens. Fulminant UC is a common cause for diagnosing IC, as classic pathologic features of UC are obscured and overlapped with features of CD such as relative, or even absolute, rectal sparing (possibly because the transverse colon is more severely involved), early fissuring ulceration, and transmural inflammation [

10]. IC has a higher prevalence in pediatric IBD. A meta-analysis of pediatric and adult IBD patients showed that 13% of children and 6% of adults with IBD were classified as IC and that IC was significantly associated with childhood onset of IBD [

11]. A retrospective analysis of 250 children found that among children diagnosed with IBD, 74 (29.6%) had diagnoses of IC either as pancolitis at diagnosis or left-sided disease that progressed to pancolitis within a mean of 6.5 years. The remaining one patient was reclassified with UC [

12]. Forty-nine (66.2%) patients maintained their diagnosis of IC after a mean follow-up of 7 years. This study noted that the clinical course of IC has not been well defined in children, and it is believed to be fraught with an increased relapse frequency and severity. Romano et al. [

13] have concluded from these data that pediatric IC might be considered a distinctive clinical entity of IBD, specifically, an aggressive and rapidly progressive disease phenotype with a higher prevalence than in adults.

Still, the atypical lymphocyte aggregation found in the resected colon, which had initially led to a suspicion of lymphoma, remained unexplained. In addition to IC, genetic factors that might have affected the patient’s condition were investigated as well. Genetic analysis found evidence of KBG syndrome, a rare genetic disorder characterized by macrodontia, distinctive craniofacial features, skeletal finding, and developmental delays sometimes associated with seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities; deletion or presence of a heterozygous pathogenic variant of the

ANKRD11 gene known to cause the syndrome confirmed the diagnosis [

14]. Although the prevalence of KBG syndrome is currently unknown, as of 2024, more than 250 patients have been described worldwide [

15]. While gastroesophageal reflux disease and constipation have been reported in some patients [

16], KBG syndrome mainly presents with neurological and skeletal manifestations. There is no established correlation between KBG syndrome and IC. No similar case has been reported. While a case of congenital aganglionic megacolon accompanying KBG syndrome has been reported [

17], the patient in our case did not have abnormalities in intestinal ganglia. However, immune dysregulation might have played a part in the abnormal reaction of lymphocytes that possibly led to perforation.

In conclusion, the presented case demonstrates that although there is no definitive relationship between colitis and KBG syndrome, acute colitis that is severe enough to cause spontaneous colon perforation might occur in patients even without IBD, malignancy, or other conditions, necessitating close monitoring of clinical symptoms. It should also be noted that IC, or fulminant colitis without a formerly known cause, could be a valid reason for genetic analysis, especially when there are other causes for suspicion (such as developmental delay and facial dysmorphism).

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.D., K.H.Y.; Data curation: Y.J.; Formal analysis: name; Methodology: K.E.N., L.C.; Project administration: K.D.; Supervision: K.D., Y.J.K., K.H.Y.; Validation: K.E.N.; Visualization: Y.J.; Writing - original draft: Y.J.; Writing - review & editing: K.D.

Fig. 1.

A 12-year-old male patient with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. (A) CT image showing diffuse dilatation of the colon with extensive pneumatosis intestinalis, (B) CT image showing free air in abdominal cavity.

CT, computerized tomography.

Fig. 2.

Gross and histologic findings. (A) Undermining ulceration of the colon. (B) Histopathologic findings of colonic ulceration (H&E stain, ×40). Black triangles indicate undermining ulceration, and arrows indicate preserved crypt architecture and absence of chronic mucosal distortion. (C) Extreme lymphoid infiltration. (D) Atypical lymphocytes found within lymphoid infiltration. (E) Sinus histiocytosis of lymph node. (F) CD68 immunohistochemistry staining shows infiltration of atypical cells in a lymph node.

H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tan SS, Wang K, Pang W, Wu D, Peng C, Wang Z, et al. Etiology and surgical management of pediatric acute colon perforation beyond the neonatal stage. BMC Surg 2021;21:212.

- 2. Kothari K, Friedman B, Grimaldi GM, Hines JJ. Nontraumatic large bowel perforation: spectrum of etiologies and CT findings. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:2597-608.

- 3. Park KY, Gill KG, Kohler JE. Intestinal perforation in children as an important differential diagnosis of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Case Rep 2019;20:1057-62.

- 4. Kim SH, Cho YH, Kim HY. Spontaneous perforation of colon in previously healthy infants and children: its clinical implication. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2016;19:193-8.

- 5. Cabrera JM, Sato TT. Medical and surgical management of pediatric ulcerative colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2018;31:71-9.

- 6. Barnes EL, Jiang Y, Kappelman MD, Long MD, Sandler RS, Kinlaw AC, et al. Decreasing colectomy rate for ulcerative colitis in the United States between 2007 and 2016: a time trend analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020;26:1225-31.

- 7. Lin CC, Wei SC, Lin BR, Tsai WS, Chen JS, Hsu TC, et al. A retrospective analysis of 20-year data of the surgical management of ulcerative colitis patients in Taiwan: a study of Taiwan Society of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Intest Res 2016;14:248-57.

- 8. Glickman JN, Bousvaros A, Farraye FA, Zholudev A, Friedman S, Wang HH, et al. Pediatric patients with untreated ulcerative colitis may present initially with unusual morphologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:190-7.

- 9. Horio Y, Uchino M, Bando T, Chohno T, Sasaki H, Hirata A, et al. Rectal-sparing type of ulcerative colitis predicts lack of response to pharmacotherapies. BMC Surg 2017;17:59.

- 10. Odze RD. A contemporary and critical appraisal of ‘indeterminate colitis’. Mod Pathol 2015;28 Suppl 1:S30-46.

- 11. Prenzel F, Uhlig HH. Frequency of indeterminate colitis in children and adults with IBD - a metaanalysis. J Crohns Colitis 2009;3:277-81.

- 12. Carvalho RS, Abadom V, Dilworth HP, Thompson R, Oliva-Hemker M, Cuffari C. Indeterminate colitis: a significant subgroup of pediatric IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:258-62.

- 13. Romano C, Famiani A, Gallizzi R, Comito D, Ferrau’ V, Rossi P. Indeterminate colitis: a distinctive clinical pattern of inflammatory bowel disease in children. Pediatrics 2008;122:e1278-81.

- 14. Morel Swols D, Foster J 2nd, Tekin M. KBG syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:183.

- 15. Bajaj S, Nampoothiri S, Chugh R, Sheth J, Sheth F, Sheth H, et al. KBG syndrome in 16 Indian individuals. Am J Med Genet A 2025;197:e63907.

- 16. Low K, Ashraf T, Canham N, Clayton-Smith J, Deshpande C, Donaldson A, et al. Clinical and genetic aspects of KBG syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2016;170:2835-46.

- 17. Choi Y, Choi J, Do H, Hwang S, Seo GH, Choi IH, et al. KBG syndrome: Clinical features and molecular findings in seven unrelated Korean families with a review of the literature. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2023;11:e2127.