ABSTRACT

-

Purpose

To report the findings of a perception survey on intestinal malrotation conducted by the Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons (KAPS) in 2021.

-

Methods

The perceptions on intestinal malrotation regarding clinical decision making of the KAPS members were collected through web-based survey.

-

Results

A total of 22 surgeons were answered for this study. The results were presented and discussed at the 37th annual meeting of KAPS, which was held in Seoul on June 18, 2021.

-

Conclusion

This study provides the clinical decisions of the KAPS members on the intestinal malrotation. The study is expected to be an important reference for improving pediatric surgeons’ understanding and treatment of intestinal malrotation.

-

Keywords: Intestinal volvulus; Pediatrics; Surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal malrotation, a congenital anomaly arising from improper rotation and fixation of the midgut during embryogenesis, is a rare but clinically significant condition. Globally, its incidence is approximately 1 in 500 to 1 in 6,000 live births, depending on the population studied [

1]. Clinically, intestinal malrotation is important due to its potential progression to midgut volvulus, a true surgical emergency. Volvulus can lead to catastrophic outcomes such as bowel necrosis, severe short bowel syndrome, or death if not promptly treated. Despite the urgency associated with symptomatic cases, the management of asymptomatic or incidentally diagnosed malrotation remains controversial [

2]. Aggressive surgical intervention may result in unnecessary risks, including surgical complications, while conservative approaches might leave the patient fatal midgut volvulus.

The perception and decision-making of pediatric surgeons regarding this condition are critical, as they directly influence patient outcomes. In international contexts, diverse management strategies have been reported, reflecting the complexity of balancing the risks and benefits [

2-

4]. Graziano et al. [

2] highlighted the variability in surgical indications based on age, anatomical findings, and symptoms. In Korea, pediatric surgeons’ perspectives on this topic have not been systematically documented, despite the increasing use of prenatal ultrasonography and advanced imaging modalities that facilitate earlier diagnosis. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring Korean pediatric surgeons’ awareness and management preferences for intestinal malrotation. By addressing these insights, we hope to contribute to evidence-based guidelines that optimize surgical decision-making and patient care.

METHODS

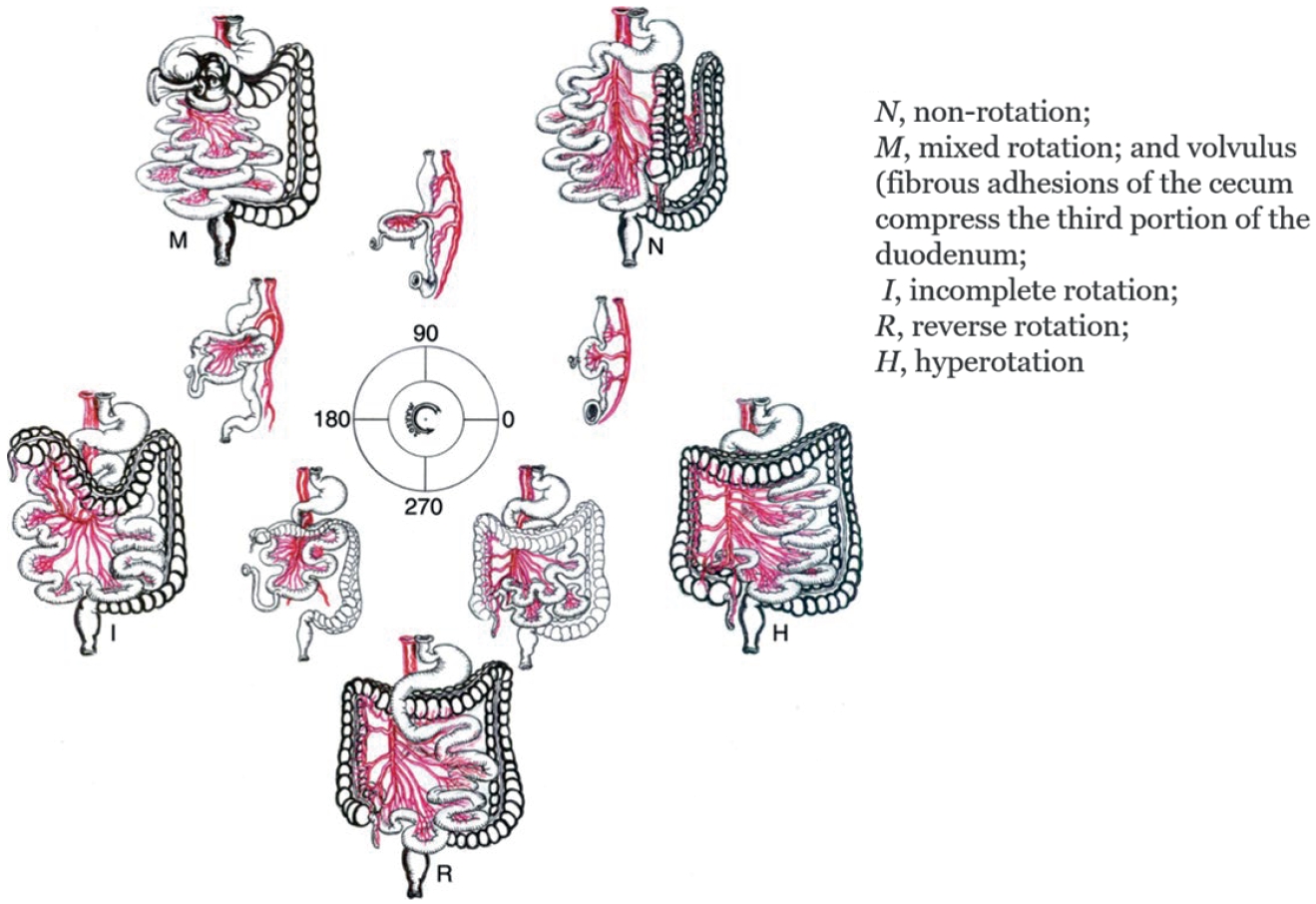

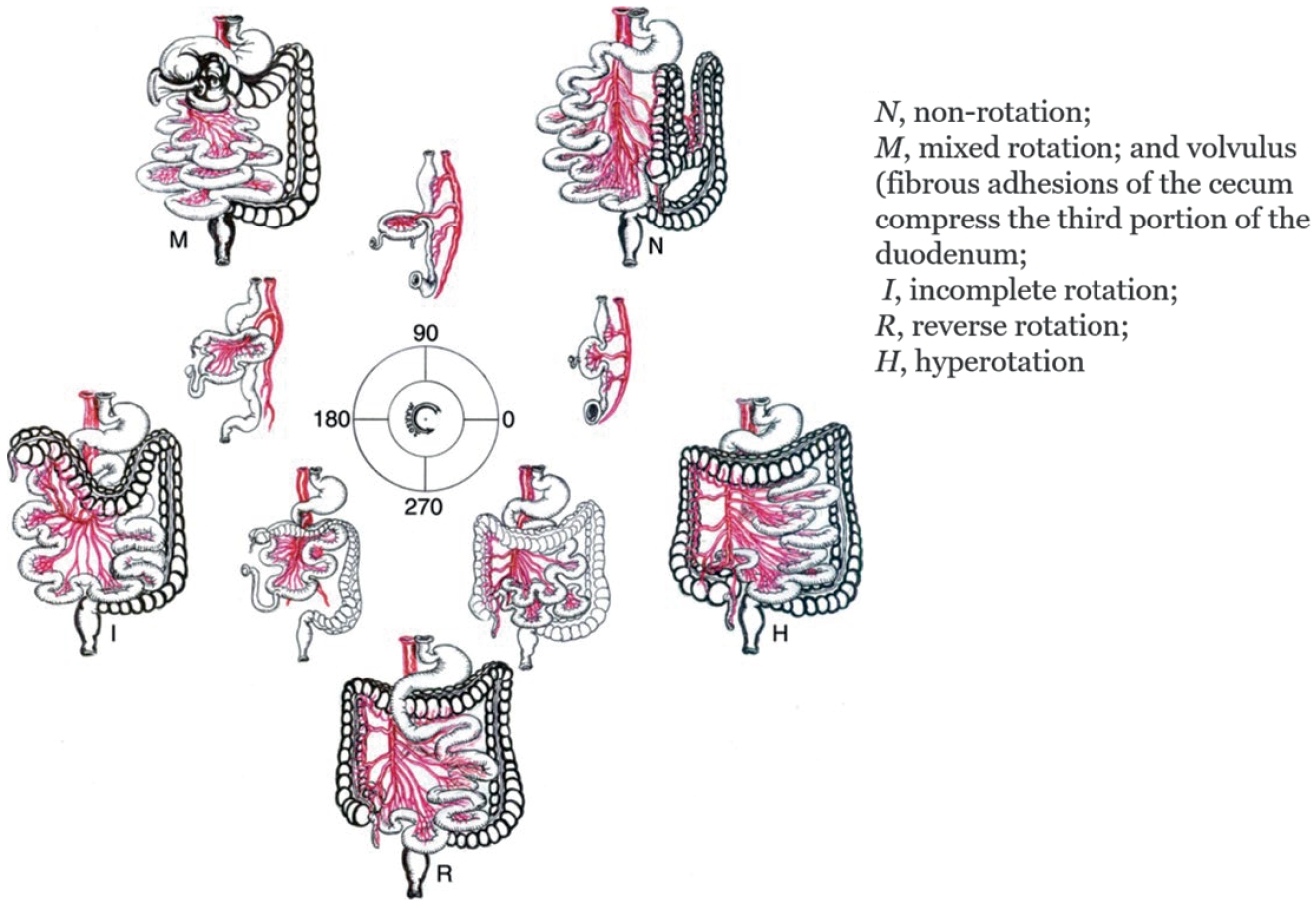

A cross-sectional survey was distributed to the Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons (KAPS) members across Korea to collect data on their clinical practices regarding intestinal malrotation. The survey included questions on the surgeons’ experience, membership qualifications, usage of diagnostic methods (e.g., abdominal sonography, X-ray, upper gastrointestinal series [UGIS], abdominal computed tomography [CT]) management for asymptomatic patients. surgical approaches (e.g., laparotomy, laparoscopy), and post-surgical follow-up duration. Malrotation type is in

Fig. 1 [

5]. Google Forms was used for data collection (

https://forms.gle/zQWbaRpLxb6TL6jNA).

RESULTS

A total of 22 surgeons across South Korea participated in this survey on the perception of intestinal malrotation.

1. Demographics of the respondents

Among the respondents, there were more men than women (male:female, 16:6) The proportion of respondents from metropolitan areas (including Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi-do) was equal to that of non-metropolitan areas (

Table 1). In terms of professional qualification among the respondent surgeons, 17 (77.3%) were regular members, while 5 (22.7%) held associate membership status, possibly reflecting varying levels of expertise or engagement in the field. The experience of surgeons in pediatric surgery revealed a wide range of expertise, with the largest group (n=9, 40.9%) having 10 to 20 years of experience, followed by 22.7% with 5 to 10 years, and 18.2% having 20 to 30 years of experience. A smaller percentage (n=3, 13.6%) had 2 to 5 years of experience, and only 4.5% had over 30 years of expertise, reflecting a distribution across different career stages.

For elective surgery, abdominal sonography was utilized in 100% of cases, reflecting its role in preoperative evaluations (

Table 2). X-rays and UGIS were equally popular, each being used in 85.2% of cases, suggesting their combined utility in confirming the diagnosis. Abdominal CT scans, however, were less commonly used, being employed in only 14.8% of cases. In contrast, during emergency cases, abdominal sonography remained the leading diagnostic tool, used in 88.9% of cases, followed by X-rays, which were utilized in 81.5% of situations. Abdominal CT scans were used more frequently in emergencies (44.4%) compared to elective preparations, while UGIS usage dropped to 22.2%, and other diagnostic tools were employed in 14.8% of emergencies.

When intestinal malrotation was detected incidentally on fetal ultrasound (US), 41.2% of surgeons answered conservative approach without immediate surgical intervention in asymptomatic cases (

Table 3). However, elective surgical intervention was chosen for 29.4% of surgeons, emphasizing its importance in preventing potential complications, while emergency surgery within one to two days was chosen from 11.8% of surgeons. For malrotation detected during abdominal surgery preparation in the post-neonatal period, elective surgery was overwhelmingly the preferred choice of action in 82.4% of surgeons, while observation without surgery and emergency operations within 1 to 2 days were each in only 5.9%. When malrotation was detected during an ongoing abdominal surgery, 88.2% of cases were managed through concurrent surgery performed alongside the planned procedure. emphasizing the practicality and efficiency of addressing malrotation during the same operation. In contrast, 11.8% of cases opted for observation. For malrotation identified during preparation for extra-abdominal surgery, 47.1% of cases were managed conservatively through observation, while 41.2% underwent elective surgical correction.

The practice of appendectomy during these procedures was widespread, with 90.9% of patients undergoing this preventive measure, compared to only 9.1% where it was omitted (

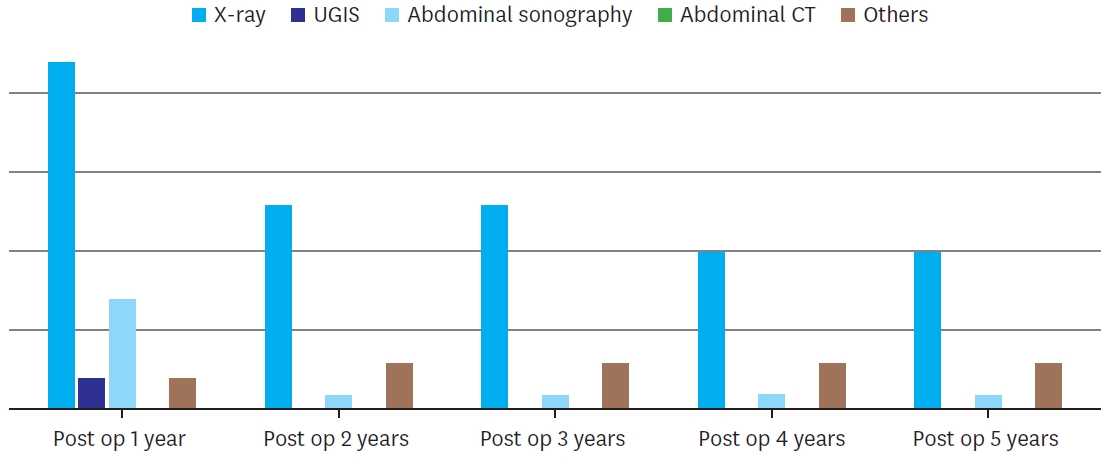

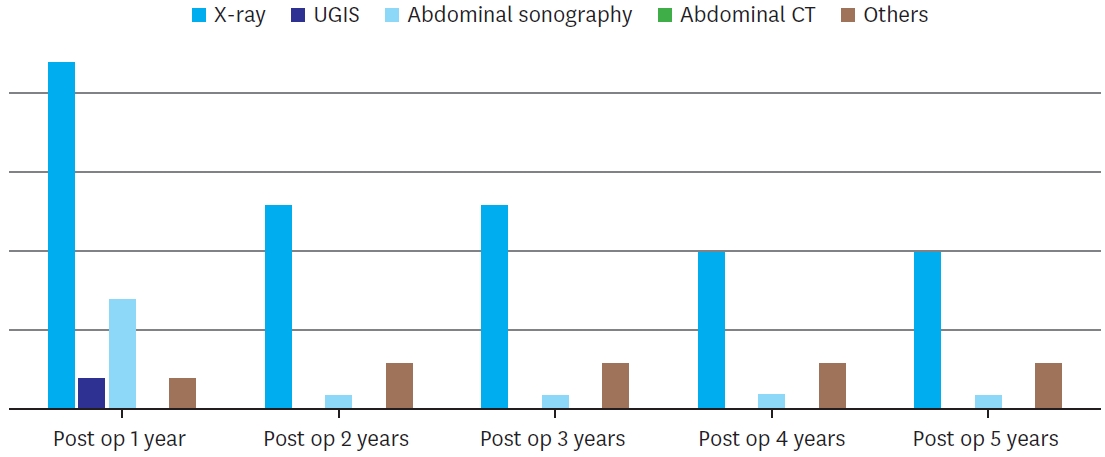

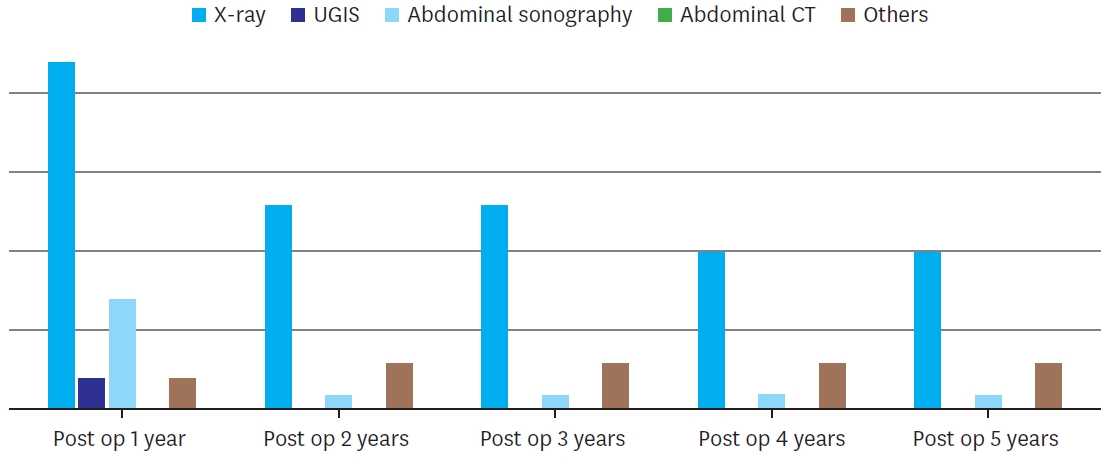

Table 4). When it came to determining surgical approaches, 77.3% of surgeons emphasized the importance of tailoring their approach based on Preoperative imaging findings, and 22.7% relied exclusively on open laparotomy. Timing for second-look surgeries was divided almost equally, with 54.5% of surgeons preferring a timeframe of 24 to 36 hours, while 45.5% opted for 48 to 72 hours, suggesting that both approaches are considered viable depending on the clinical circumstances and the patient’s condition. Regarding postoperative care, the follow-up duration after surgery showed that the majority of cases (54.5%) involved a follow-up period of 1 year, while both 3- and 5-year follow-ups were reported in 13.6% of cases each. Meanwhile, 18.0% of cases opted for other durations, perhaps reflecting tailored follow-up strategies based on individual patient needs or outcomes. Tools for follow up was presented in

Fig. 2. X-ray was the diagnostic tool of choice for follow up regardless of the period. No respondents used abdominal CT for follow up.

DISCUSSION

Over the past 30 years of pediatric surgery surveys, this is the first nationwide investigation into intestinal malrotation. This research focuses on the perspectives of pediatric surgeons regarding intestinal malrotation.

Midgut volvulus, often associated with intestinal malrotation, is considered a true emergency in pediatric surgery, requiring immediate surgical intervention. Delays in treatment can lead to necrosis of the entire small bowel and portions of the colon, resulting in death or severe morbidity, such as short bowel syndrome [

6]. However, not all cases of intestinal malrotation involve volvulus. Hence, unnecessary aggressive management could lead to overtreatment, causing complications or large scars. This study investigates the management approaches for incidentally detected intestinal malrotation.

For cases detected on fetal US, about 40% responded that they would proceed with observation without surgery. If detected during preparations for abdominal surgery after the neonatal period, approximately 80% indicated that they would perform surgery concurrently. Similarly, about 90% responded they would operate if discovered during surgery. For cases incidentally identified during preparations for non-abdominal surgeries, 40% suggested elective operations. In summary, most respondents indicated that if abdominal surgery is required after the neonatal period, they would address malrotation during the same procedure. Conversely, if no abdominal surgery is involved, many opted not to intervene.

Graziano et al. [

2] conducted a systematic review on the management of asymptomatic malrotation. They suggested that if intestinal malrotation is incidentally detected, the presence of symptoms, congenital heart defects, and age should guide decisions. UGIS should be used to confirm whether the malrotation involves a narrow mesenteric stalk, nonrotation with a broad mesentery, or atypical anatomy with duodenal malposition. If the anatomy remains uncertain, diagnostic laparoscopy may be performed, although its benefit diminishes with age. They recommended prophylactic Ladd’s procedure for asymptomatic cases in younger patients. A study they reviewed using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample found that prophylactic Ladd’s procedures provided the greatest benefit in children under one year, with benefits persisting until 20 years of age [

7]. Beyond 20 years, the risk of surgery-related complications outweighed the benefits, discouraging prophylactic Ladd's operations. However, Spigland et al. [

8] argued that true asymptomatic cases do not exist and recommended laparotomy regardless of age.

Although there are various types of intestinal malrotation, their classification is not widely used among respondents in this study (29.4%). Xiong et al. [

9] recently classified 332 adult malrotation patients into 10 types based on CT findings, considering the positions of the duodenum, jejunum, and cecum. Only 1.8% of cases with normal duodenal rotation showed malrotation. The most common type involved partial duodenal rotation, with the jejunum and cecum positioned on the right. The second most common type was duodenal nonrotation, with the jejunum and cecum also on the right. Notably, 22.0% of cases with a normal superior mesenteric artery/superior mesenteric vein axis still exhibited malrotation. Statistically significant differences were observed in type distributions between surgically treated and conservatively managed groups, with the duodenal nonrotation type more prevalent in surgical cases.

UGIS was more frequently performed in scheduled surgeries than in emergencies, likely due to time constraints. However, a study reported that of nine volvulus patients, three showed normal findings on US, indicating that US lacks sufficient sensitivity for diagnosing volvulus [

10].

A survey on laparoscopic versus open surgery approaches showed that 22.7% preferred open surgery, while 77.3% decided based on imaging findings. When volvulus or bowel ischemia was suspected, 81.3% opted for open surgery. Literature supports laparoscopic surgery in older patients but recommends open surgery when volvulus is present [

2].

Appendectomy was performed in 90.9% of cases. The Ladd’s procedure, a standard for intestinal malrotation, includes appendectomy. Al Smady et al. [

11] conducted an online survey with 102 pediatric surgeons (60% response rate) and reported that 12% did not perform appendectomy, a rate similar to Korea. Surgeons who performed appendectomy cited the abnormal appendix position, which complicates future appendicitis diagnosis, as the primary reason. Those who avoided it cited the potential need for the appendix in the future.

Follow-up periods after surgery varied among surgeons, ranging from 1 year to adulthood. Most (54.5%) followed patients for 1 year. El-Gohary et al. [

12] reported complications in 14 out of 123 patients (8.7%) after Ladd’s procedure, most commonly adhesive small bowel obstruction (9 cases). Recurrent volvulus was observed within one month of surgery, necessitating reoperation. In a median 5-year follow-up, most patients were asymptomatic, but 6 experienced chronic constipation, and two reported nonspecific recurrent abdominal pain [

12]. No clear evidence exists on the optimal follow-up period, which likely depends on individual patient conditions.

When asked about the management of asymptomatic cases of specific malrotation types, most respondents recommended observation for all except type M, which had a higher likelihood of requiring surgery due to associated symptoms or potential complications.

In conclusion, intestinal malrotation presents with diverse symptoms and types. Management decisions should consider the patient’s underlying conditions, symptoms, and imaging findings comprehensively.

NOTES

-

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Fig. 1.

Malrotation type.

Adapted from ‘Intestinal malrotation’ by Sotiropoulou [

5].

Fig. 2.

Follow up tools according to period.

UGIS, upper gastrointestinal series; CT, computed tomography.

Table 1.Demographics of the respondents (n=22)

Table 1.

|

Category |

Option |

Values |

|

Sex |

Male |

16 (72.7) |

|

Female |

6 (27.3) |

|

Province (hospital area) |

Metropolitan area |

11 (50.0) |

|

Non-metropolitan area |

11 (50.0) |

|

Membership qualification |

Associate |

5 (22.7) |

|

Regular |

17 (77.3) |

|

Pediatric surgery experience |

2-5 yr |

3 (13.6) |

|

5-10 yr |

5 (22.7) |

|

10-20 yr |

9 (40.9) |

|

20-30 yr |

4 (18.2) |

|

Over 30 yr |

1 (4.5) |

Table 2.

Table 2.

|

Scenario |

Diagnostic methods |

Percentage (%) |

|

Elective surgery preparation |

Abdominal sonography |

100 |

|

X-ray |

85.2 |

|

Upper gastrointestinal series |

85.2 |

|

Abdominal CT |

14.8 |

|

Others |

3.7 |

|

Emergency surgery preparation |

Abdominal sonography |

88.9 |

|

X-ray |

81.5 |

|

Abdominal CT |

44.4 |

|

Upper gastrointestinal series |

22.2 |

|

Others |

14.8 |

Table 3.Management for incidentally detected intestinal malrotation

Table 3.

|

Scenario |

Management approach |

Percentage (%) |

|

Detected during prenatal period |

Observation without surgery |

41.2 |

|

Elective operation |

29.4 |

|

Emergency operation within 1-2 days |

11.8 |

|

Others |

17.6 |

|

Detected during abdominal surgery preparation (post-neonatal period) |

Elective operation |

82.4 |

|

Observation without surgery |

5.9 |

|

Emergency operation within 1-2 days |

5.9 |

|

Others |

5.9 |

|

Detected during abdominal surgery (post-neonatal period) |

Concurrent operation with planned surgery |

88.2 |

|

Observation without surgery |

11.8 |

|

Treat later as separate surgery |

0.0 |

|

Detected during extra-abdominal surgery preparation (post-neonatal period) |

Observation without surgery |

47.1 |

|

Elective operation |

41.2 |

|

Emergency operation within 1-2 days |

0.0 |

|

Others |

11.8 |

Table 4.Clinical decision making for intestinal malrotation

Table 4.

|

Scenario |

Management options |

Percentage (%) |

|

Appendectomy |

Yes |

90.9 |

|

No |

9.1 |

|

Open vs. Laparoscopy |

Determined by imaging findings |

77.3 |

|

Open only |

22.7 |

|

Timing for second-look surgery |

24-36 hr |

54.5 |

|

48-72 hr |

45.5 |

|

Follow-up duration |

1 yr |

54.5 |

|

3 yr |

13.6 |

|

5 yr |

13.6 |

|

Others |

18.0 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Svetanoff WJ, Srivatsa S, Diefenbach K, Nwomeh BC. Diagnosis and management of intestinal rotational abnormalities with or without volvulus in the pediatric population. Semin Pediatr Surg 2022;31:151141.

- 2. Graziano K, Islam S, Dasgupta R, Lopez ME, Austin M, Chen LE, et al. Asymptomatic malrotation: Diagnosis and surgical management: an American Pediatric Surgical Association outcomes and evidence based practice committee systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:1783-90.

- 3. Cohen Z, Kleiner O, Finaly R, Mordehai J, Newman N, Kurtzbart E, et al. How much of a misnomer is “asymptomatic” intestinal malrotation? Isr Med Assoc J 2003;5:172-4.

- 4. Mehall JR, Chandler JC, Mehall RL, Jackson RJ, Wagner CW, Smith SD. Management of typical and atypical intestinal malrotation. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:1169-72.

- 5. Sotiropoulou M. Intestinal malrotation. In Carneiro F, Chaves P, Ensari A, eds, ddPathology of the gastrointestinal tract. Encyclopedia of pathology. Cham: Springer; 2017, pp 401-4.

- 6. Strouse PJ. Disorders of intestinal rotation and fixation (“malrotation”). Pediatr Radiol 2004;34:837-51.

- 7. Malek MM, Burd RS. The optimal management of malrotation diagnosed after infancy: a decision analysis. Am J Surg 2006;191:45-51.

- 8. Spigland N, Brandt ML, Yazbeck S. Malrotation presenting beyond the neonatal period. J Pediatr Surg 1990;25:1139-42.

- 9. Xiong Z, Shen Y, Morelli JN, Li Z, Hu X, Hu D. CT facilitates improved diagnosis of adult intestinal malrotation: a 7-year retrospective study based on 332 cases. Insights Imaging 2021;12:58.

- 10. Zerin JM, DiPietro MA. Superior mesenteric vascular anatomy at US in patients with surgically proved malrotation of the midgut. Radiology 1992;183:693-4.

- 11. Al Smady MN, Hendi SB, AlJeboury S, Al Mazrooei H, Naji H. Appendectomy as part of Ladd’s procedure: a systematic review and survey analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 2023;39:164.

- 12. El-Gohary Y, Alagtal M, Gillick J. Long-term complications following operative intervention for intestinal malrotation: a 10-year review. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:203-6.

, Min Jeng Cho2, Yu Jeong Cho2, Yoon Mi Choi2, Jae Hee Chung2, Seok Joo Han2, Jeong Hong2, Eunyoung Jung2, Ki Hoon Kim2, Soo-Hong Kim2, Cheol-Gu Lee2, Nam-Hyuk Lee2, Ju Yeon Lee2, Sanghoon Lee2, Suk Bae Moon2, Young-Hyun Na2, So Hyun Nam2, Chaeyoun Oh2, Jin Young Park2, Junbeom Park2, Tae-Jin Park2, Jae Ho Shin2, Joonhyuk Son2, Hyun-Young Kim3

, Min Jeng Cho2, Yu Jeong Cho2, Yoon Mi Choi2, Jae Hee Chung2, Seok Joo Han2, Jeong Hong2, Eunyoung Jung2, Ki Hoon Kim2, Soo-Hong Kim2, Cheol-Gu Lee2, Nam-Hyuk Lee2, Ju Yeon Lee2, Sanghoon Lee2, Suk Bae Moon2, Young-Hyun Na2, So Hyun Nam2, Chaeyoun Oh2, Jin Young Park2, Junbeom Park2, Tae-Jin Park2, Jae Ho Shin2, Joonhyuk Son2, Hyun-Young Kim3 , The Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons

, The Korean Association of Pediatric Surgeons